Not long after the guns of the Civil War fell silent, many former combatants took up the pen to re-fight their battles on paper. The conflict had been a defining moment in the lives of thousands of young soldiers. Major General Judson Kilpatrick (1836-1881), arguably one of the most colorful figures to emerge from war, longed for a more visual reminder of things past.

Not long after the guns of the Civil War fell silent, many former combatants took up the pen to re-fight their battles on paper. The conflict had been a defining moment in the lives of thousands of young soldiers. Major General Judson Kilpatrick (1836-1881), arguably one of the most colorful figures to emerge from war, longed for a more visual reminder of things past.

And in 1878, on the bucolic fields of his northern Deckertown New Jersey farm, “Little Kil” as he was affectionately called by his West Point classmates, sought to recreate scenes familiar to the old veterans. General Kilpatrick would stage the first major reenactment of a Civil War battle.*

Known to some as “Kill-Cavalry” for his alleged abuse of men and horses during the war, not every cavalryman agreed with this infamous sobriquet. “That he has done some rash things all must acknowledge,” wrote one trooper in the 2nd New York Cavalry, “but that he has done much to give a name to the Cavalry of the Union Army must also be acknowledged.”

After graduation from West Point in the May 1861 class, the future general fought as a captain in Abram Duryée‘s Zouaves at the Battle of Big Bethel, recruited the Harris Light Cavalry as its lieutenant colonel, led a brigade and division of cavalry in the Gettysburg campaign, and initiated a failed 1864 raid on Richmond.

After graduation from West Point in the May 1861 class, the future general fought as a captain in Abram Duryée‘s Zouaves at the Battle of Big Bethel, recruited the Harris Light Cavalry as its lieutenant colonel, led a brigade and division of cavalry in the Gettysburg campaign, and initiated a failed 1864 raid on Richmond.

He completed his Civil War career as commander of Major General William T. Sherman’s cavalry in the March to the Sea and Carolina campaigns. Despite several battlefield embarrassments and three combat wounds, “Kill-Cavalry” managed to attain the rank of major general by age 27.

From his early days at West Point, Kilpatrick nourished a keen interest in politics. It can be argued that his meteoric military career was integrally linked to cultivated political connections.

But by 1878 Kilpatrick’s political aspirations were dismal. Despite repeated attempts, he failed to garner the New Jersey gubernatorial nomination and had changed political parties twice.

But by 1878 Kilpatrick’s political aspirations were dismal. Despite repeated attempts, he failed to garner the New Jersey gubernatorial nomination and had changed political parties twice.

As a backer of Rutherford B. Hayes’ 1876 presidential bid, “Little Kil” had bungled his campaign responsibilities, losing Hayes’ confidence and costing him a coveted job in the new administration.

But the former cavalryman’s fertile mind was not idle. Now a gentleman farmer, he conceived the idea of an enormous encampment for Grand Army of the Republic veterans. The three day event would include military parades, appearances by famous generals and politicians, speeches, a play authored by Kilpatrick himself, even a sham battle between the veterans and the New Jersey National Guard.

At first preparations hummed along briskly, with New Jersey Governor George B. McClellan agreeing to provide troops, tents, arms and equipment. A New York City caterer was engaged to serve special guests at the general’s farmhouse. The famous showman P.T. Barnum provided a giant tent to accommodate 5,000 people. A grandstand, fresh water aqueduct and guardhouse were constructed. Kilpatrick would pay for the free event by charging vendors for booth space.

The first day’s scene was reminiscent of the war itself as scarred faced, empty sleeved veterans arrived at the crowded railroad station accompanied by state militia units in full dress uniforms. Some 10,000 people made their way two and a half miles from the train depot to the farm.

The first day’s scene was reminiscent of the war itself as scarred faced, empty sleeved veterans arrived at the crowded railroad station accompanied by state militia units in full dress uniforms. Some 10,000 people made their way two and a half miles from the train depot to the farm.

After they trudged up the dusty roads, the throng quickly became aware of shortages in food and tents. “We didn’t have a thing to eat,” moaned a member of the New Jersey National Guard, “until my company formed, and each man putting in thirty cents, we bought our supper.”

Beer, however, was not in short supply. Apparently the much-touted aqueduct system failed, so participants took advantage of the 10,000 kegs of brew on hand to quench their thirsty throats.

“Camp Kilpatrick,” likened by the press as “one vast beer garden,” had its share of gamblers, pickpockets, roulette wheels, sword swallowers and other raucous performers. Adding innuendo to Kilpatrick’s reputation, just a mile from the general’s farmhouse, was a large tent staffed by “shameless women.”

Day two included a dress parade, political speeches by one-legged General Dan Sickles and a performance of the Kilpatrick’s new play Allatoona. When actors forgot their lines, the general, hidden off stage, was ready with his prompter’s book. The evening concluded with a serenade dedicated to Mrs. Kilpatrick and a grand fireworks display.

Day two included a dress parade, political speeches by one-legged General Dan Sickles and a performance of the Kilpatrick’s new play Allatoona. When actors forgot their lines, the general, hidden off stage, was ready with his prompter’s book. The evening concluded with a serenade dedicated to Mrs. Kilpatrick and a grand fireworks display.

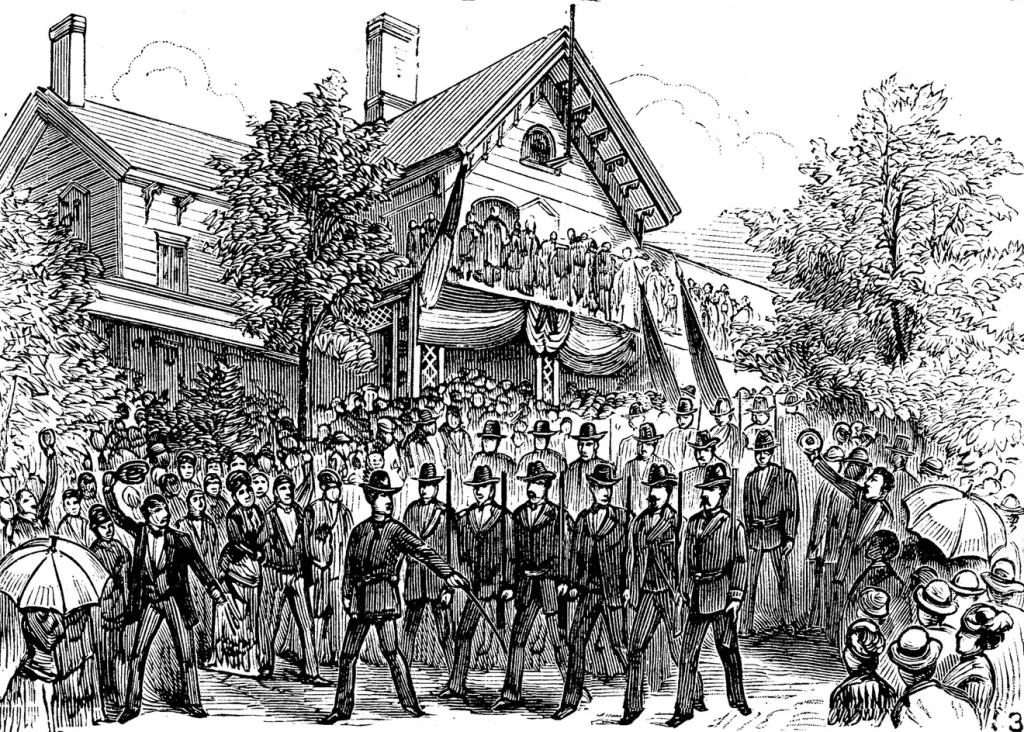

The final day of the celebrated August encampment dawned cool and cloudless. By noon, some 30,000 spectators had jammed Kilpatrick’s pastures for the much heralded sham battle.

A boom of cannon signaled the opening a 1,500-man battle. The veterans, acting the part of Confederates, were posted on a hill. The state militia attacked from its position on the field below, capturing the battery.

The old soldiers counterattacked with flags flying, musketry rattling and artillery roaring. Hand-to-hand combat in retaking the field pieces left many reenactors bleeding from small wounds.

Suddenly, General Kilpatrick emerged on his piebald charger, dashing into the melee with a flag of truce. Recognizing a supreme dramatic moment, “Little Kil,” standing up in his stirrups, declared for all to hear that his long standing wish had been fulfilled: he had recreated the past days of glory. The crowd responded with uproarious cheers.

The sham battle thus concluded, the men marched back to camp. In typical theatric style, Kilpatrick stood on his porch, his arm in a sling, feigning a wound as the troops filed by him.

For one season at least the general’s farm was destroyed: his grain and hay supply consumed, the cornfield trampled, the orchard ruined, fences down. Cynics who speculated that he hosted the reenactment for profit were grossly mistaken. A New York paper sarcastically commented that “this little entertainment will cost him $5,000 when all the bills are in. But what are filthy dollars to a man of sentiment?”

For one season at least the general’s farm was destroyed: his grain and hay supply consumed, the cornfield trampled, the orchard ruined, fences down. Cynics who speculated that he hosted the reenactment for profit were grossly mistaken. A New York paper sarcastically commented that “this little entertainment will cost him $5,000 when all the bills are in. But what are filthy dollars to a man of sentiment?”

Kilpatrick, however, remained unmoved by the criticism. In this respect, his reenactment was a perfect reflection of its creator: great fanfare, unfulfilled expectations, political hyperbole, a generous dose of theater, some success and an undercurrent of depravity.

* The reenactment was not the first as even before the fighting ended, veterans recreated battles to remember their fallen dead, raise funds, and educate the public about what had occurred.

Read more about the Civil War and New York State.

Illustrations, from above: Judson Kilpatrick by Mathew Brady (National Archives); Kilpatrick as a Cavalryman during the war; Kilpatrick as a politician in the 1870s; Reenactors pass Judson Kilpatrick’s farm; a rare stereoview of the 1878 reenactment; and the site of the reenactment in Deckertown (courtesy Hidden New Jersey).