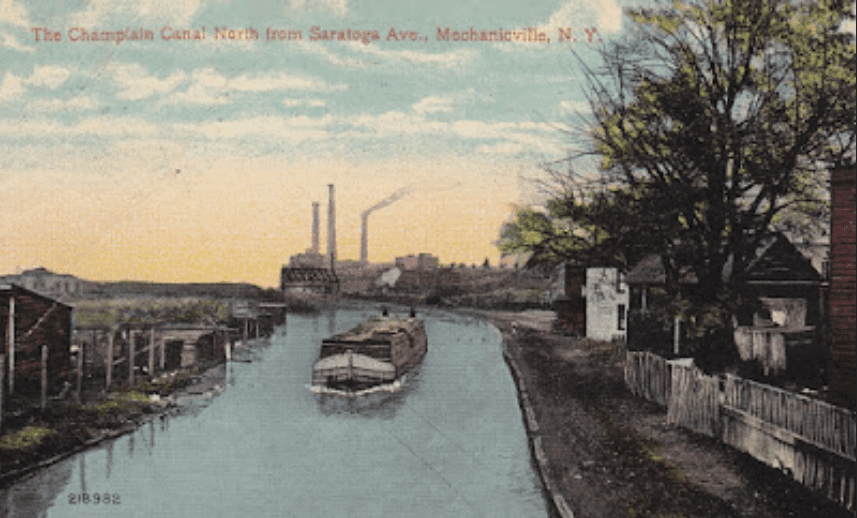

On a cold December night in 1906, when the Champlain Canal still bisected the village of Mechanicville, in Saratoga County, NY, a 61-year-old woman living alone in a second-floor apartment on Canal Street heard a cry for help.

On a cold December night in 1906, when the Champlain Canal still bisected the village of Mechanicville, in Saratoga County, NY, a 61-year-old woman living alone in a second-floor apartment on Canal Street heard a cry for help.

Going out onto her porch overhanging the not-yet-frozen waterway, she saw a man floundering in the stagnant water. She leaped over the railing into the canal below and swam to the man’s side. Her cries for help, along with his, did bring help and the man’s life was saved.

Who was this courageous woman who put her life on the line for a total stranger? She was called “Mrs. Cats” by neighborhood children because she kept at least 40 of the creatures as well as a squirrel in her home.

A reclusive woman, she had few friends, and her life before Mechanicville and nearby Stillwater was completely unknown to the neighbors amidst whom she had lived off and on for around 30 years.

After her heroic dive into the canal, she went back to her houseful of cats and her solitary existence. Mrs. Cats died eleven years later, alone on Canal Street, on April 17, 1917. She was cremated and her ashes entombed at Oakwood Cemetery in Troy, NY.

What was then known of Annie Blanche Scott Sokalski was that she was a widow, but all she would ever say about her late husband was that he was a true gentleman and a hero of the Civil War. She had cared for a friend, Kate Hewitt of Stillwater, whose fiancé, General John Reynolds, had died at Gettysburg, until Kate’s death. She had for a time tutored the children of a family in Hemstreet Park, a village just north of Lansingburgh.

A member of St. Luke’s Church, she was gifted on the piano, and her neighbors, the Leylands, let her play their piano. She had directed an operetta, “Red Riding Hood,” at the Academy in Stillwater. She had supported herself selling bicycles in Stillwater and Mechanicville, and later became a door to door peddler. It was a meager existence, a lonely life, a hard life for a woman alone. It would be half a century before the rest of Annie Sokalski’s story would be known.

Annie was born in Little Rock, Arkansas in 1845 to the wealthy, slave-owning Scott family. She was well-educated and sang in her church choir. She also played the organ at church, and unlike most genteel southern belles, she could ride a horse as well as a man could.

When the Confederates States of America was being organized in opposition to the United States, the Scotts supported Arkansas’ secession from the Union, and Annie’s uncle and cousin became officers in the Confederate Army. After Ulysses S. Grant’s victory at Vicksburg, Mississippi on July 4, 1863, Union troops moved into Little Rock and occupied the capital city for the duration of the war. One of the officers in the occupation was Captain Sokalski.

George O. Sokalski, a career military man was born in Troy and had graduated from West Point Military Academy in 1861, a classmate of George Armstrong Custer.

George O. Sokalski, a career military man was born in Troy and had graduated from West Point Military Academy in 1861, a classmate of George Armstrong Custer.

Somehow, in the midst of war, Annie met the young captain and the two fell in love. Two days after Christmas in 1864, the 19-year-old girl and the United States military officer were married in Little Rock. Three days later, Sokalski was ordered to the frontier. Annie, disowned by her family for marrying the enemy, went west with him.

Annie embraced the frontier life. She acquired thirteen hunting dogs. Her two favorites were named Romeo and Juliet. She learned to shoot a gun and became an expert marksman. She was said to be a better rider than most cavalrymen.

The story goes that soon after the war had ended, dressed in wolf skins and wearing a riding habit with wolf tails hanging from her skirt, she galloped across the parade ground at Fort Kearney past a stunned General William Tecumseh Sherman who thought she was a Native American.

Sokalski, who had been promoted to the rank of Lt. Colonel, was next sent to Post Cottonwood in Nebraska Territory, the popular name for Fort McPherson. The fort was built after the 1862 Dakota War to protect travelers along the Oregon and California Trails, between Fort Kearny and Colorado.

Sokalski was apparently a highly-regarded young officer, experienced in all phases of combat, having served in 56 engagements in the war, but he was a bit of a hothead. Being a West Point trained officer, he resented being under the command of officers who had come up as volunteers and political appointees. He soon got himself in trouble for insubordination and was court-martialed.

On May 1, 1866 Sokalski’s trial began. He would plead his own case, assisted by his feisty young wife. The case went on for eight days, but when the time came for Annie to take the stand on her husband’s behalf, the judge declared her incompetent to give evidence.

On May 1, 1866 Sokalski’s trial began. He would plead his own case, assisted by his feisty young wife. The case went on for eight days, but when the time came for Annie to take the stand on her husband’s behalf, the judge declared her incompetent to give evidence.

The case was lost. Sokalski was dishonorably discharged on July 10th. After an appeal was rejected, he lost heart. But Annie was not about to give up. She appealed by every means available to her, and on October 26, her husband was reinstated as a cavalry officer. The success was not to be enjoyed, however as the 27-year-old colonel died several weeks later at Fort Laramie in Dakota Territory and was buried there.

Annie took her husband’s body home to Troy in a covered wagon and had him quietly buried in Mount Ida Cemetery. She returned to Little Rock where she taught school, but, rejected by her family, left Arkansas and moved to Saratoga County in the mid 1870s, living in Stillwater and Mechanicville for most of the next forty years. She tended to her many cats, occasionally made beautiful music on the Leylands’ piano and peddled trinkets door to door.

The story of Annie Sokalski came to light largely through the efforts of Major General Charles G. Stevenson, working for the Polish National Alliance in the 1960s. With the approaching centennial of the end of the Civil War, the PNA was anxious to find the true burial site of Colonel Sokalski, who had been the first American of Polish descent to graduate from West Point.

Thanks to meticulous research and some persistent physical searching, the location of the colonel’s grave was finally found in Mt. Ida by a young boy scout who was part of the party searching the cemetery for the grave.

Thanks to meticulous research and some persistent physical searching, the location of the colonel’s grave was finally found in Mt. Ida by a young boy scout who was part of the party searching the cemetery for the grave.

Annie’s ashes were removed from the vault at Oakwood and brought to Mt. Ida on September 11, 1965. In a proper and fitting ceremony honoring Colonel Sokalski, and with prayers offered by Rev. Robert G. Field of St Luke’s Church, Annie Blanche Scott Sokalski finally rejoined the true love of her life.

The story of this fiercely independent woman of incredible courage and commitment, a giver of self, a humble and unassuming one-time southern belle who died alone at home alongside the canal in downtown Mechanicville, begs us to wonder… do we ever really know our neighbors?

Sandy McBride is a native of Mechanicville. Writing has always been her passion, and she has won numerous awards for her poetry and has written feature stories for The Express weekly newspaper. She has published four books of feature stories and two poetry collections, and a children’s historical novel on the Battles of Saratoga entitled “Finding Goliath and Fred.”

Illustrations, from above: The Champlain Canal at Mechanicville, NY; George O. Sokalski’s commissioning certificate, signed by Abe Lincoln; a portrait of Sokalski; and Annie and George Sokalski’s memorial at Mount Ida Cemetery.