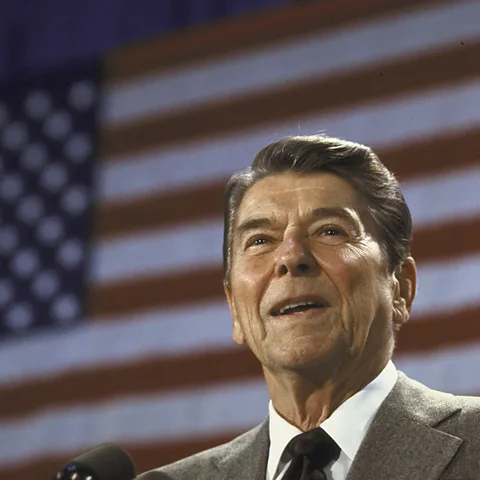

Meanwhile, President Reagan’s criminal justice reforms – tougher punishments, expanded law enforcement powers, and increased incarceration – came wrapped in uncompromising rhetoric. ”The American people want their government to get tough and go on the offensive,” the president said in 1986, as he signed an anti-drug bill into law. “And that’s exactly what we intend, with more ferocity that ever before.”

The character of John Doe in Seven caricatures that attitude, although Andrew Hartman, an academic historian and expert on the culture wars of the late 20th Century, tells the BBC it would be wrong to suggest that the film sided with either right-wing or left-wing political parties. “Seven itself doesn’t sermonise,” he says, noting that when Democrat Hillary Clinton was the first lady in the 1990s, she “took up the tough-on-crime mantle”. In 1994, Clinton declared: “We need more police, we need more tougher prison sentences for repeat offenders… We need more prisons to keep violent offenders for as long as it takes to keep them off the streets.” And Clinton was hardly associated with the Reaganite right. “These ideas about criminality ebb and flow across political parties,” says Hartman.

In creating John Doe in Seven, Walker drew on notions of sin, damnation, and divine punishment that were increasingly common in the public sphere. Prominent evangelicals like Jerry Falwell Sr, for instance, a Baptist minister and founder of the Moral Majority, railed against “the pornographers, the smut peddlers, and those who are corrupting our youth”. Meanwhile James Dobson, founder of the global Christian ministry Focus on the Family, sought to restore a God-fearing obedience in children through corporal punishment on the theory that “pain in a marvellous purifier”. And televangelist Pat Robertson predicted impending Armageddon based on “certain signs, or clues, that His coming is approaching”.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesHartman sees parallels between this language and the language in Seven – as exaggerated and distorted as it is when it comes from John Doe. “As the religious right reasserted itself at the centre of culture and the American ethos, it blamed a permissive culture of hedonism for shattering families, igniting the Aids crisis, and unleashing delinquency,” he says.