The late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in America are often described as a “Golden Age” of book collecting. Driven by a desire for cultural aura, wealthy individuals and prestigious institutions acquired unique manuscripts and incunabula as well as rare printed books. Well-stocked bookcases

The late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in America are often described as a “Golden Age” of book collecting. Driven by a desire for cultural aura, wealthy individuals and prestigious institutions acquired unique manuscripts and incunabula as well as rare printed books. Well-stocked bookcases

were considered an emblem of wisdom. Part of Europe’s literary heritage was shifted across the Atlantic to the United States.

The antiquarian book trade flourished; specialist auction houses reflected the spending power of the era’s elite. Some critics have referred to this collecting rage as a “gentle madness.” It was worse than that.

Rich collections on display in a grand private setting became a statement of economic power. As opulence and tastelessness appear to be related, the mania was corruptive and impacted negatively upon the judgment of book creators and bibliophiles alike.

The Great Omar

Having served in the Austrian Army, tailor Felix Sangorski arrived in London from his native Kraków, Poland, in 1860. A year later he married Lydia Clark, a South London seamstress and umbrella maker, at St Annes Church in Soho. Francis Longinus Sangorski was born on March 15, 1875, in St Giles, Camden.

In 1897, Francis was a student at the Central School of Arts and Crafts, established by the London County Council (LCC) in the previous year and inspired by the legacy of William Morris and his associates. There he met fellow student George Sutcliffe. Both concentrated their studies on bookbinding. In October 1901, in spite of unfavourable economic conditions, they started a business in a rented attic room at Bloomsbury Square.

The firm soon became known for bold and daring designs of multi-colored leather bindings. In 1907, Francis Sangorski met John Harrison Stonehouse, manager of Sotheran’s bookshop in London which could pride itself on a history going back to 1761. That year Henry Sotheran acquired a bookseller’s

shop in the city of York.

By 1803 the business had moved to London under guidance of Thomas Sotheran, Henry’s nephew and former apprentice. Sangorski told Stonehouse about his ambition to bind a particular book in a manner “such as had never been seen before.”

The book concerned was Edward Fitzgerald’s 1859 translation into English of Omar Khayyam’s classical Rubaiyat, an edition published in Boston in 1884 by Houghton Mifflin that included fifty-five captivating illustrations by Elihu Vedder.

The book concerned was Edward Fitzgerald’s 1859 translation into English of Omar Khayyam’s classical Rubaiyat, an edition published in Boston in 1884 by Houghton Mifflin that included fifty-five captivating illustrations by Elihu Vedder.

After some persuasion, Stonehouse agreed. He sensed a potential marketing opportunity if the book’s presentation would coincide with the coronation of George V in June 1911 at Westminster Abbey.

In 1909, he commissioned Sangorski & Sutcliffe to create a jeweled, gilt-edged binding for the book. In an era that witnessed an artistic vogue for “Orientalism,” the Persian poet’s quatrains (four-line poems) exploring themes of love, wine, death and fate were popular amongst Victorian readers. After two years of intense labor at his Holborn workshop, Sangorski finished the binding in 1911.

Measuring forty by thirty-five centimeters, the “Great Omar” was encrusted with 1,050 jewels that included specially cut rubies, topazes, amethysts, turquoises and emeralds.

The book consisted of six panels: the front and back covers, the inside of the two boards – known as “doublures” – and two end leaves adorned with plants, a snake in an apple tree, a skull with a poppy growing from an eye socket, and Persian symbolic patterns.

The front cover was adorned with three golden peacocks with spread tail feathers. In some cultural traditions, the “eye” on a peacock’s

feather represents a bad omen that may inflict misadventure (in Jewish mythology the “evil eyes” are associated with Lilith, the mother of various demons). In theater circles peacocks were believed to bring poor luck to performers. The great book itself would be haunted by tragedy.

Presented with the finished product, Stonehouse was impressed, describing it as the “most remarkable specimen of binding ever designed.” It was put on offer for an extraordinary £1,000 (the equivalent of just over $137,000 today). The price was not the only issue that hampered its sale.

First choice for its acquisition had been given to John Fortescue, the Royal librarian and archivist at Windsor Castle, but he refused to handle a work that he considered to be both inappropriate and vulgar. Many booklovers agreed. They hated this piece of tacky Edwardian bling, rejecting the “Great Omar” as an embarrassing misjudgment.

Titanic & The Blitz

Gabor Weiss was born into a Jewish family in January 1861 at Balassa-Gyarmath, a small town north of Budapest. After a faltering career and failed marriage, he moved to America in 1894, settling in Boston where he changed his name to Gabriel Wells. A protégé of Professor William James, he spent three years at Harvard University being employed as a tutor in Psychology and German.

Wells then changed course and established a bookselling business in Manhattan. He would become one of America’s most important rare book dealers in the first half of the twentieth century, acting as President of the Antiquarian Booksellers’ Association in 1930.

His success is reflected in the changes of his business address: from an office at 128 East 23rd Street to larger quarters at 489 Fifth Avenue, opposite the New York Public Library (NYPL). A decade later he moved into offices at 145 West 57th Street, never needing to publish a catalogue of his stock.

On a visit to London in 1911, Gabriel frequented Sotheran’s branch at 43 Piccadilly where he saw the “Great Omar” on display. He was impressed and made an unsuccessful offer. Further negotiations between London and New York City stalled. Wells proved to be a cunning deal maker.

In the end and in some desperation, the booksellers decided to auction the book. On March 29, 1912, it went under the hammer at Sotheby’s without a reserve. Wells was the winner. His London agent paid £405 for the treasure which was subsequently insured for £500 to make the crossing to Manhattan on board the RMS Titanic on her maiden voyage.

Little is known of the book’s journey as Wells and his agent were secretive about arrangements in an attempt to avoid having to pay custom duties on arrival. It has been suggested that the “Omar” was safeguarded by Harry Elkins Widener, a bibliophile from Pennsylvania who was returning to the United States from a stay in London. Like the book, he did not survive the disaster. His mother commissioned the building of Harvard University’s Widener Library in his memory.

A few weeks after the ship’s sinking tragedy struck again. On holiday in Sussex with his family, Francis took a dip in the sea but was knocked off his feet by a strong current. Unable to swim he drowned. Sangorski & Sutcliffe continued as a company in spite of the loss of its co-founder.

In 1924, Sutcliffe’s nephew Stanley Bray joined as an apprentice. Eight years later, he came across the original drawings and tooling patterns for the “Omar” and decided to re-create the great work.

The binding was finished just as the Second World War engulfed Europe. During the Blitz, the book was placed in a “secure” vault at Fore Street, City of London. The area was bombarded heavily shortly after and almost completely leveled during the raids. The safe was eventually traced, but the heat had ruined the book into a black mass of melted leather and charred pages. Ironically, the firm’s premises in Poland Street, Soho, were not damaged in the war.

As many of the jewels had survived, Bray was determined to create a third version. Much of the work (some 4,000 hours of toil) was carried out in the 1980s after his retirement. The finished work is now held in London at the British Library where a digital copy of “Omar III” has been made available.

As many of the jewels had survived, Bray was determined to create a third version. Much of the work (some 4,000 hours of toil) was carried out in the 1980s after his retirement. The finished work is now held in London at the British Library where a digital copy of “Omar III” has been made available.

At times it takes a disaster to rattle belief systems. The sinking of the Titanic made an impact on both sides of the Atlantic and forced a rethink of values. To social commentators the sad event was a result of excessive human pride and presumption. Edward Stuart Talbot, Bishop of Winchester, declared in April 1912 that the fate of the ship was a “mighty lesson against our confidence and trust in power, machinery and money.”

The original Rubaiyat rests on the bottom of the mid-Atlantic, a sunken symbol of brilliant craftsmanship, overriding ambition and loss of purpose. Nearly a decade later, the name of Gabriel Wells returned to divide bibliophiles and booklovers once again.

Mutilators

English-born Joseph Sabin had been an immensely successful bookseller at 84 Nassau Street, Manhattan, since 1864. He was also the author of A Dictionary of Books Relating to America (known as “Bibliotheca Americana”) in twenty-nine volumes, the standard bibliography of literature pertaining to early American history. The qualification “In Sabin” (with reference number) or “Not in Sabin” is an indicator of a publication’s rarity or otherwise.

During his long career, Sabin handled the sale of numerous valuable book collections. At a Sotheby’s auction in London on November 9, 1920, he made his final major acquisition (lot no. 70), the defective “Mannheim copy” of the Gutenberg Bible formerly owned by Maria von Sulzbach, wife of Carl Theodore, Electoral Prince of the Palatinate. In 1921, Sabin sold the Bible on to Gabriel Wells.

Wells opted to break up the damaged work and sell the leaves separately. Each of them was slip-cased in a blue goatskin portfolio carrying the words “A Leaf of the Gutenberg Bible.” The folder was accompanied by an essay penned by his friend, the Pennsylvanian industrialist and book collector Alfred Edward Newton, entitled “A Noble Fragment, Being a Leaf of the Gutenberg Bible.”

The sale of individual leaves gave institutions the opportunity to purchase parts that were missing in their own copies of the Bible. A personal donation by Wells allowed the New York Public Library to complete its imperfect “James Lenox” copy, the first Gutenberg that had been brought to America in 1847.

The sale of individual leaves gave institutions the opportunity to purchase parts that were missing in their own copies of the Bible. A personal donation by Wells allowed the New York Public Library to complete its imperfect “James Lenox” copy, the first Gutenberg that had been brought to America in 1847.

Its arrival in New York Harbor had been the stuff of folklore. James Lenox’s European agent who had handled the transfer of this costly item instructed officers at Custom House to pay tribute to Gutenberg by removing their hats.

The Wells project was a lucrative undertaking, but he set a precedent that motivated other booksellers to follow his example. His bibliophilic vandalism heralded an era of shameless pursuits whereby dealers and researchers removed individual manuscript leaves which were sold either separately or re-

assembled in the shape of a leaf book.

One of Wells’s leaves was acquired by Otto Ege. Dean of the Cleveland Institute of Art and lecturer on the History of the Book at Western Reserve University, the latter was a self-proclaimed “leave cutter.”

He systematically eliminated pages from some fifty illuminated medieval manuscripts and divided them into forty compilation boxes, commonly referred to as the “Otto Ege Portfolios.” They were sold worldwide, raising a small fortune.

In 1938, Ege published a defiant essay entitled “I Am a Bibliocast” in the first issue of the short-lived “hobbies” magazine Avocations. Allowing students to get the “thrill and understanding” that comes from, literally, touching the past justified the practice. As few of them could ever hope to hold a complete manuscript, many were enabled to own a leaf for themselves.

In 1938, Ege published a defiant essay entitled “I Am a Bibliocast” in the first issue of the short-lived “hobbies” magazine Avocations. Allowing students to get the “thrill and understanding” that comes from, literally, touching the past justified the practice. As few of them could ever hope to hold a complete manuscript, many were enabled to own a leaf for themselves.

With a sniff of European snobbery, American booksellers were accused of cultural vandalism. There was however one problem with this charge. Leaf books did not originate in the United States. They were a British invention.

In his Biographical History of England (1769), the Rev. James Granger had popularized the practice of inserting leaves and prints into books of reference that did not belong to the book itself, but were pertinent to the subject treated.

His critics introduced the term “grangerizing” for this bizarre pursuit, but the real passion for leaf books belongs to the late nineteenth century. Initially, damaged books were dismantled for academic purposes as the study of individual leaves would enhance knowledge of the early stages of book production.

Even John Ruskin subscribed to this theory and acted accordingly. One folio in his bookcase was John Obadiah Westwood’s Miniatures and Ornaments of Anglo-Saxon and Irish Manuscripts (1868) from which he had ripped out the plates for use in his lectures. His medieval manuscripts were similarly

mistreated. On December 30, 1853, he wrote in his diary: “Set some papers in order and cut out some leaves from large missal.” Ruskin was a mutilator too.

In 1880 William Blades, a collector-preserver of the works of William Caxton, England’s first printer, published The Enemies of Books in which he expressed outrage at book mutilation (reprinted in 2014 by Cambridge University Press). Throughout the 1870s he turned his ire against the casual mistreatment of rare books.

In 1880 William Blades, a collector-preserver of the works of William Caxton, England’s first printer, published The Enemies of Books in which he expressed outrage at book mutilation (reprinted in 2014 by Cambridge University Press). Throughout the 1870s he turned his ire against the casual mistreatment of rare books.

In spite of natural threats such as water, fire, dust and vermin or insects (bookworms, rats or flies), human beings were the worst enemies. Damage was done by professionals, collectors or binders to the structure of the book; bigots and censors threatened its contents.

Blades introduced the term “biblioclast” – a person who mutilates or destroys books – in our critical jargon. In today’s political climate, the word has regained an unfortunate relevance.

Read more about books and book history.

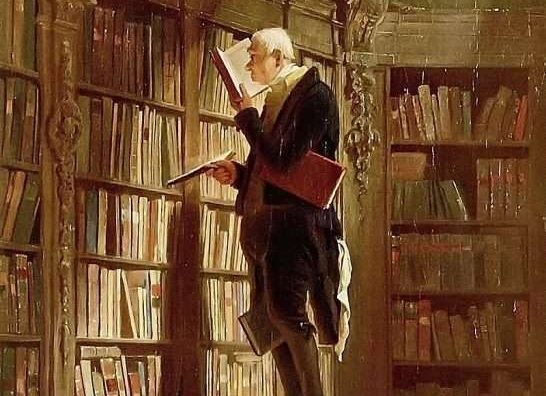

Illustrations, from above: A detail from Carl Spitzweg’s “The Bookworm,” ca. 1850. (Museum Georg Schäfer, Schweinfurt; a second version of the painting is housed at the Central Library of Milwaukee, Wisconsin); The Elihu Vedder Rubaiyat (Boston: Houghton Mifflin and Company, 1886); The third version of the “Great Omar,” held at the British Library; Advertisement for the “Noble Fragments” (Columbia University Library); Otto Ege’s controversial defence of book mutilation in first issue of the magazine Avocations (New York, March 1938); and William Blades’ The Enemies of Books, 1880 (Cambridge University Press reprint, 2014).