Shortly after the Supreme Court handed down the Civil Rights Cases in 1883 [which declared the Civil Rights Act of 1875 unconstitutional], a mass meeting was called for Lincoln Hall in the nation’s capital. Two prominent Republican orators — one black and one white — were the featured speakers. Frederick Douglass — the runaway slave who had become an avid student of the Constitution in the course of his career as an abolitionist — spoke first.

Shortly after the Supreme Court handed down the Civil Rights Cases in 1883 [which declared the Civil Rights Act of 1875 unconstitutional], a mass meeting was called for Lincoln Hall in the nation’s capital. Two prominent Republican orators — one black and one white — were the featured speakers. Frederick Douglass — the runaway slave who had become an avid student of the Constitution in the course of his career as an abolitionist — spoke first.

Robert G. Ingersoll [born in 1833 in Yates County, NY] — highly valued as a Republican orator despite his outspoken atheist views — closed the program. In some ways, the event was a political rally, similar to others that had characterized both the long battle against slavery and the heady early days of Reconstruction.

But this day was different, for everyone present in the hall named for the nation’s “Great Emancipator” knew that it marked the end of an era — and not a satisfying conclusion at that. It was a wake without any happy accompanying festivities.

Douglass sensed that new life would not quickly follow that being mourned. Resigned that a renewal of racial progress would occur only

long after his lifetime, he urged his hearers to not react out of understandable anger. He specifically cautioned against violence.

“Patient reform is better than violent revolution,” Douglass said, sounding very much as he had in Glasgow when he had distanced himself from John Brown in the winter of 1859–60.

But in that prior event, he had been optimistic and looking forward to the election of an antislavery president. Progress had then been anticipated. Working within the constitutional system then promised that slavery itself might be destroyed.

By contrast, in 1883, Douglass saw no grounds for immediate optimism, but still cautioned against any action that might produce an even greater defeat than the one represented in the Court’s decision.

By contrast, in 1883, Douglass saw no grounds for immediate optimism, but still cautioned against any action that might produce an even greater defeat than the one represented in the Court’s decision.

Ingersoll too urged his hearers to remain law-abiding and work for peaceful change. The fact that both men stressed this point indicated a fear that some might respond to the Court’s action in unpredictable ways.

Charles Fairman has analyzed intersectional white newspaper support of the decision and has found that it was overwhelming. Some of the editorial commentary from Republican papers expressed in words the tremendous obstacle that Douglass sensed confronted his race at the close of the nation’s first civil rights struggle.

The New York Tribune suggested that the voided Civil Rights Act of 1875 that had required equal access to public accommodations such as railroad cars, theaters, hotels, and amusement parks had only served “to irritate public feeling.”

The Portland Oregonian offered that nothing was really lost as “social rights” can never be legislated — an opinion seconded by the Milwaukee Sentinel.

The Chicago Tribune advised that “time and better education,” not civil rights legislation, was the most effective way to fight racial prejudice, which it naively predicted would be eliminated in a generation.

Perhaps worst of all, the recorded private thoughts of Justice Joseph Bradley [born in 1813 in Albany County, NY], who delivered the Court’s majority opinion in the case, indicated that he viewed legislation requiring racial integration, such as that required in the Civil Rights Act of 1875, as a form of “slavery.”

The Court’s decision was no Dred Scott decision that could rally Republicans in popular opposition. To the contrary, a white Republican Supreme Court had relieved an interracial party of responsibility for civil rights legislation that lacked the support of an intersectional majority.

“This decision takes from seven millions of people the shield of the Constitution,” said Ingersoll, speaking for the minority of white Republicans angered by the Court’s action. “It leaves the best of the colored race at the mercy of the meanest white.”

Both Douglass and Ingersoll grieved that most whites refused to admit that there was an injustice involved. Douglass articulated that the decision was in favor of “slavery, caste and oppression.”

Both Douglass and Ingersoll grieved that most whites refused to admit that there was an injustice involved. Douglass articulated that the decision was in favor of “slavery, caste and oppression.”

He confessed to feeling as he had when the Court in 1857 had handed down the Dred Scott decision, making this comparison in order to emphasize the continuing “conflict between the spirit of liberty and the spirit of slavery.” The slave-holding republic, he conceded, was gone. But “the spirit or power of slavery” lived on.

In slavery times, Douglass emphasized, the Court had strongly supported slavery, manipulating the Constitution in order to protect the institution in ways never intended by the Founding Fathers. Yet following the formal death of slavery, the Court was only lukewarm for liberty.

He looked forward to a time when “a Supreme Court of the United States… shall be as true to the claims of humanity, as the Supreme Court formerly was to the demands of slavery.”

He recalled how the Court had upheld the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, which was blatantly unconstitutional given its casual disregard of the Bill of Rights. In that case, the Court had concocted an original intent of the Constitution’s fugitive slave clause, without any evidence to support its claim.

Yet, in the Civil Rights Cases, the Court clearly ignored the well-documented intent of the authors of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments. In a case involving freedom, the Court’s decision absolved the states from dedicating themselves to a national standard, whereas in a case involving fugitive slaves the outcome had been otherwise.

The United States did not deserve to be called a nation, charged Douglass, for under the state-centered interpretation of the Court the federal government was incapable of protecting “the rights of its own citizens upon its own soil.”

Why had this decision been made? The answer to him was clear. White Americans did not identify with the daily oppression experienced by

black people in a land dominated by white people.

When white men observed a hotel clerk refusing lodging to black female travelers, they did not see such treatment as equivalent to their own wives and daughters being abused in a similar manner. Big trouble loomed, he warned, if common decency continued to be so casually discarded.

Sounding as Lincoln had in his Second Inaugural, Douglass suggested: “No man can put a chain about the ankle of his fellow man, without at last finding the other end of it fastened about his own neck… The evil day may be long delayed, but so sure as there is a moral government of the universe, so sure will the harvest of evil come.’’

In his time at the lectern, Ingersoll emphasized that the Court’s decision invited whites to inflict “involuntary servitude” upon blacks. This, he said, had been outlawed by the Thirteenth Amendment, which partially supported the Civil Rights Act of 1875.

“A man is in a state of involuntary servitude,” he noted, “when he is forced to do, or prevented from doing, a thing, not by the law of the State, but by the simple will of another.”

By this interpretation, every refusal of service by a person involved in running a public accommodation constituted an act of “involuntary servitude.” His argument necessarily ignored the reality that the enactment of the Fourteenth Amendment had encouraged a far more restricted meaning for the Thirteenth Amendment than he presented.

In any case, the audience left Lincoln Hall at the conclusion of the meeting with no assurances of any coherent plan to reverse the Court’s ruling.

Ironically, the Civil Rights Cases produced one apparent benefit by assuring white southern politicians that they had nothing to fear from Republican Henry Blair’s plan to enact federal aid for the improvement of impoverished southern public-school systems, black as well as white.

By weakening the federal government’s ability to direct and oversee issues of racial equity, the Court’s decision persuaded many state-centered southern Democrats that no good reason existed for them to oppose the Blair bill. Indeed, after the decision, some of Blair’s closest allies came from the ranks of southern Democrats.

[The Blair Education Bill was a federal funding proposal aimed at supporting primary and secondary education which sought to allocate federal funds to states based on the number of “illiterates” in each state, which favored Southern states, which had higher rates of illiteracy due to the legacy of slavery.]

Nevertheless, the leadership of the Democratic party in the house remained firmly in opposition and managed to kill Blair’s proposals through-out the 1880s.

Finally, in 1888, the Republican party acquired majorities in both houses of Congress and won the presidency as well. The divided government, which had ushered in the end of Reconstruction, gave way to Republican control. Yet, nothing was done to ameliorate the wretched condition of most African Americans, suffering in an environment of quasi-slavery.

In 1890, when the Blair bill failed to pass, it was clear that the failure was due to northern Republican apathy. Former president Rutherford B. Hayes, who had presided over the formal end of Reconstruction but had thereafter committed himself to the cause of African American education in the southern states, was crushed by his party’s behavior.

Calling others devoted to the cause to meet with him at Lake Mohonk in Ulster County, New York, Hayes tried to set a tone that would inspire at least this minority to work for social change despite the Republican Congress’s clear lack of interest.

Calling others devoted to the cause to meet with him at Lake Mohonk in Ulster County, New York, Hayes tried to set a tone that would inspire at least this minority to work for social change despite the Republican Congress’s clear lack of interest.

Hayes emphasized white America’s obligation to the freedmen: “We are responsible for their presence and condition on this continent. Having deprived them of their labor, liberty, and manhood, and grown rich and strong while doing it, we have no excuse for neglecting them… In truth, their welfare and ours, if not one and the same, are inseparable. These millions who have been so cruelly degraded must be lifted up, or we ourselves will be dragged down.’’

Hayes’s appeal was too late. That same year, in addition to killing the Blair bill, the Republican Congress failed to pass Henry Cabot Lodge’s proposal to force the South to conduct honest elections. Mississippians interpreted these two actions as Republican encouragement to treat the “Negro question” any way they saw fit.

Beginning in a convention writing a new state constitution, they fashioned a program both to disfranchise African Americans and to reduce

even the scanty educational opportunities then available to blacks. Over the next several years, the rest of the South moved in the same direction.

In 1890, and for many years thereafter, whites concentrated on deepening the degradation of African Americans rather than engaging in any program of assistance. At the outset of the twentieth century, lynching blacks at times seemed to become a blood sport in parts of the nation.

Whites often justified exceptional cruelty toward blacks with pseudoscientific proofs that African Americans were permanently “unassimilable.”

In the first generation experiencing it, formal emancipation did not produce a meaningful freedom for most former slaves. One hundred years later, much has changed; but in spite of significant progress, race relations remain in a state of unease and mutual distrust, punctuated by occasional outbursts of mass violence and daily incidents of ugly individual confrontation.

To this day, aspects of the slave-holding republic’s legacy remain, both in whites unable to fathom the depth of African American grievances and in blacks deeply alienated by a long history of oppression.

To this day, aspects of the slave-holding republic’s legacy remain, both in whites unable to fathom the depth of African American grievances and in blacks deeply alienated by a long history of oppression.

The bitter harvest, referred to both in Abraham Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address of 1865 and in Frederick Douglass’s well-reasoned forecast of 1883, unhappily promises to continue well into the future.

Don E. Fehreenbacher is the author of The Slaveholding Republic: An Account of The United States Government’s Relations to Slavery (Oxford University Press, 2001), from which this essay is excerpted. It was annotated by John Warren.

Read more about slavery in New York.

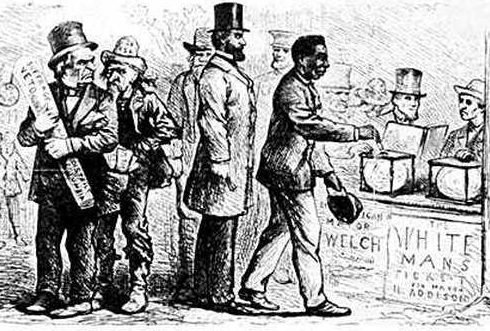

Illustrations, from above: A19th century Civil Rights cartoon; Frederick Douglass, between 1880 and 1890, photo by George Kendall Warren; “Proceedings of the Civil Rights Mass-Meeting held at Lincoln Hall,” 1883; Mohonk Mountain House in 1900 (Library of Congress); and civil rights protests in the 1960s and 2000s.