In the 1870s, the starch mill owned by Nicholas Bullis in the hamlet of Suckertown on the Little Chazy River was noted for the profusion and cheapness of its starch. Local lore said the young men in the area had their shirt collars starched to an unusual stiffness, and they became known as “Stiff Collars.”

In the 1870s, the starch mill owned by Nicholas Bullis in the hamlet of Suckertown on the Little Chazy River was noted for the profusion and cheapness of its starch. Local lore said the young men in the area had their shirt collars starched to an unusual stiffness, and they became known as “Stiff Collars.”

If you wanted to know whether an someone was a resident of Suckertown, you only had to look at their shirt collar, and the question would be answered.

In the second half of the nineteenth century, not all potatoes raised were destined for the table. Most were sent to starch mills and every town in Clinton County had at least one.

Luckily, the three main ingredients for starch production were to be found in abundance nearby – a plentiful supply of potatoes, running water to provide the power and wood to dry the separated starch into powder.

Luckily, the three main ingredients for starch production were to be found in abundance nearby – a plentiful supply of potatoes, running water to provide the power and wood to dry the separated starch into powder.

After the Civil War, there was a rise in industrialization, and with the advent of the railroad in the county in the 1850s, the product was easily transported to larger manufacturing areas. High fashion and customs in the 1800s celebrated stiff clothing and so required tons of potato starch.

Clinton County farmers realized the potential of growing potatoes and so that became a welcome way to make money. After processing, the finished concentrated product became more valuable and thus more practical to ship.

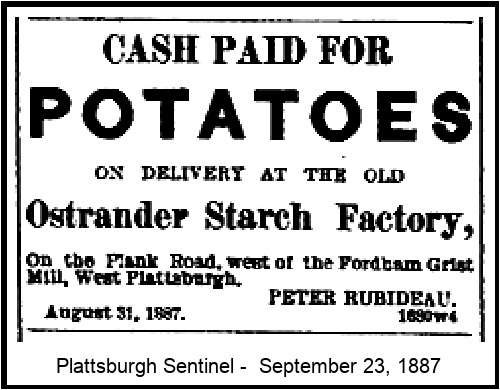

Potato yields in the county were from 50 to 200 bushels per acre depending on the type of potato. In anticipation of the coming crop, starch factory owners flooded newspapers with ads telling how much they were paying per bushel.

In the late 1800s, when potatoes were harvested, many villages in the North County had wagons lined up at the starch mills ready to be emptied.

Some starch mills, such as the one owned by Nathan Lapham of the town of Peru, had the capacity to process 200 tons of potatoes or about 40,000 bushels between September and January when the crop was in a good condition for handling. Nathan continued to produce starch until the mill burned in 1889 and it was not rebuilt.

Potato starch was extracted from the cells of potatoes which contained starch grains. To extract the starch, the potatoes were passed through a crushing machine, and the grains were released from the destroyed cells.

The starch was left to settle out of solution then dried to a white powder which could be used in cooking, laundry, and other industrial applications such as wallpaper adhesive, textile sizing and even in photographic processes. Starch came in many colors from ecru to white which was used for clothing, often with blue coloring or borax added.

Often starch mills were built in the same vicinity as sawmills, stave factories and grist mills where there was abundant waterpower. One such mill was mill was built in 1870 in Wrightsville on the Military Turnpike in the Town of Clinton.

Messrs. Humphrey and Boomhower built an extensive butter factory and starch mill on the Marble River where the Ogdensburg and Lake Champlain Railroad had a bridge. Nothing can be seen there now except a dip in Route 11.

Mill owners urged farmers to bring in their potatoes as soon as possible because, once sprouted or frozen, they were not good for the production of starch. The byproduct of the starch-making process was either spread on the fields as fertilizer for the next year’s crop or was dumped in the river downstream from the mill.

Starch production required a great deal of water for boiling and evaporation and so the mills were always built on rivers and close to sources of wood for the furnaces. Later in the century, some mills relied on steam engines instead of waterpower to run the crushers.

Although the interiors of the mills must have been unbearably hot and humid, many of them burned to the ground during the course of business only to be rebuilt because there was a need for them and there was so much money to be made.

In 1866, the Ostrander starch drying house burned in West Plattsburgh and with it, about twelve tons of starch. It was rebuilt and production continued.

In 1866, the Ostrander starch drying house burned in West Plattsburgh and with it, about twelve tons of starch. It was rebuilt and production continued.

After the starch mill burned in 1868 in Ellenburg Center, it was immediately rebuilt to benefit the mill owner and the farmers who relied upon the money paid to them for their potatoes.

For one four-day period in 1888, the starch factory in Ellenburg Center took in 12,000 bushels of potatoes at the price of fifteen cents a bushel. In one day, over one hundred teams unloaded.

The 1870 fire in the Jenkins and Scribner starch factory in Saranac 8,000 bushels were burned, but “before the smoke of the ruins had passed off,” timber was being drawn to the site for a new structure.

The starch mill in West Chazy owned by Fayette North burned with the loss of fifteen tons of starch and 4,000 bushels of potatoes. He transported the potatoes that weren’t burned to another mill that he owned in East Chazy.

It wasn’t unknown for starch mills to be owned by men from big cities who had local men manage them. Such was the case of a mill in Moffittsville, which for a time, was owned by a Boston firm – Lyon and Vose. It had a capacity for using 60,000 bushels per season and employed six men.

In October of 1870, there was a bumper crop of potatoes and Messrs. North and Bullis of Chazy were processing between 500 and 1,000 bushels each. The price per bushel that year was at an all-time high – 50 cents per bushel – a nice bonus for the farmers. The usual price per bushel was between 15 and 40 cents depending on the quality.

The potato starch mills continued to be profitable for several decades, but with the changes in fashion, the increasing use of corn starch and the discovery of new products that could replace potato starch, there was a decline in the number of starch mills in the county By the early 1900s, no more starch was made and the buildings were put to other uses.

Julie Dowd is Trustee Emeritus of the Clinton County Historical Association.

Illustrations, from above: Advertisement for potatoes for potato starch; a starched collar from the Clinton County Historical Association portrait collection; and a map showing Ellenburg Center’s starch factory, 1856 (published by O.J. Lamb of Philadelphia).