A longitudinal study of early census data tracking Black families in the towns and villages that would eventually make up Putnam County, New York, has led me to many questions and curiosities. But none bigger than Hercules.

A longitudinal study of early census data tracking Black families in the towns and villages that would eventually make up Putnam County, New York, has led me to many questions and curiosities. But none bigger than Hercules.

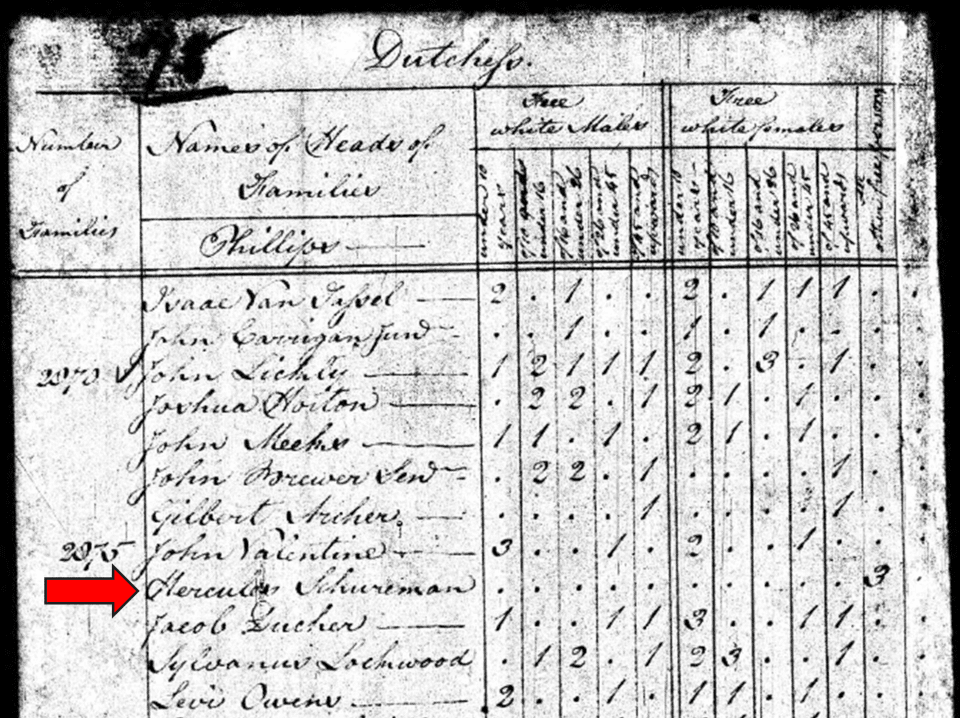

In the 1800 Federal Census, Hercules Schureman was listed as the head of a household of three in Philipstown, which was then made up of today’s Philipstown and Putnam Valley in Putnam County.

He and his family were recorded as “All Other Free Persons,” one of only seven households throughout the region that currently makes up Putnam County (after it broke off from Dutchess County in 1812), consisting of independent Black residents. By the 1810 census, the Schureman family was gone and their residency trail grows cold.

It was a curious case. When and from where did Hercules come to Putnam County? Was he formerly enslaved, and if so, how and when had he earned his freedom? Could he have served in the American Revolution?

It was a curious case. When and from where did Hercules come to Putnam County? Was he formerly enslaved, and if so, how and when had he earned his freedom? Could he have served in the American Revolution?

As if guided by the Fates (pun intended), I soon found Hercules in the National Archives Record Administration’s (NARA) Revolutionary War pension applications. Here, his story, much like his namesake, takes on hardships, tasks, and strength of mythological proportions.

(For some reason, Ancestry’s file on Hercules has much better, clearer files, see “Schurema,” U.S., Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land Warrant Application Files, 1800-1900 – Ancestry.com)

In the forty-four pages of affidavits, exhibits, and correspondence, we learn that Hercules was born in Yonkers, in Westchester County, and at the beginning of the American Revolution, was enslaved by a man named Jonathan Archer in Sugar Loaf, a hamlet in Orange County, New York.

Hercules’ testimony states that he believed Archer was a Tory, and that one day while his “master” was away from home, a group of Continental soldiers on leave tasked Hercules with directing them to the home of one of the soldier’s relatives in the “Stirling Mountains.” Unbeknownst to Hercules, he was aiding deserters of the American cause.

Soon after safely guiding the deserting soldiers to their destination, Hercules was taken into custody by “Captain Crane,” who was said to have served under Colonel William Smallwood.

To prove he was not a Tory and loyal to America, Hercules was tasked by Captain Crane with guiding him and his men to where he had taken the soldiers the day before. The deserters were ultimately captured, along with other Tories in the area.

Hercules was then recruited as a witness and promised his freedom for his contribution, continuing in service with Crane’s company.

Schureman’s pension application further explains that he was in service for several years. He includes accounts of skirmishes with the enemy in the Sterling Mountains (part of the Ramapo Mountains); service as a scout in this region between Smith’s Clove and Fort Montgomery; a wound from a bayonet received in a skirmish at Paramus; marching with one of General Smallwood’s regiments that showed up too late for the Battle of Brandywine; and then marching to Springfield where they “had an engagement with the British.” He claimed that after the war was over, he returned to Sugar Loaf with discharge and freedom papers courtesy of the Continental Army.

Once again facing Jonathan Archer, Hercules presented his papers and they were immediately seized, never to be returned. According to his testimony, Hercules was once again enslaved by Archer and eventually sold to a man named John Hinchman, who then sold him to a man named Zacharias Price. Price traded him off to his brother Francis Price.

By 1795, now in Newtown, Sussex County, New Jersey, Hercules bought his freedom from Francis Price. The manumission, dated April 14, 1795, is recorded as “Exhibit A” in Hercules’ pension application. It reads, “that a Negroman slave Named Hercules Schureman together with his wife Named Rose and their child, Peter aged about Eleven months shall and may become Free having manumitted, Emancipated, Enfranchised & set free.”

By 1795, now in Newtown, Sussex County, New Jersey, Hercules bought his freedom from Francis Price. The manumission, dated April 14, 1795, is recorded as “Exhibit A” in Hercules’ pension application. It reads, “that a Negroman slave Named Hercules Schureman together with his wife Named Rose and their child, Peter aged about Eleven months shall and may become Free having manumitted, Emancipated, Enfranchised & set free.”

Hercules purchased their freedom for the “sum of One Hundred and Thirty pounds…..Spanish mill Dollars at Eight Shillings Each,” a very substantial amount at that time.

Within five years of buying freedom, Hercules and his family are “All Other Free Persons” appearing in the 1800 Philipstown census. But why there?

One thought is, there’s a hint in the 1830s pension affidavit submitted by John Peterson, a friend in the city of New York who claimed to know Hercules for over 23 years and was well aware of his stories of service, especially that of the deserters being captured.

Peterson was acquainted with one Captain Crane who had commanded a company of Militia during the Revolution and resided at Carmel, Putnam County. He had the occasion to go to “Carmel Town” and once while there, corroborated Hercules’ association with Crane.

Although pensions on state and federal level had been made available as early as 1778, Peterson stated that Hercules did not apply earlier because he’d been “able to maintain himself.” Perhaps it was Hercules’ connection with Crane that brought him and his family, just across the Hudson River, to nearby Putnam County following his manumission.

Another thought is that when we look back at the 1800 census of “Phillips” as it was recorded, another household was under the name Gilbert Archer. Perhaps Hercules continued in service to the Archer family, possibly a relative of Jonathan Archer?

Although only in Putnam for a short time – long enough to be enumerated – Hercules soon found himself living in the 5th Ward of the city of New York, today’s lower Manhattan.

Even though he was living “free,” subsequent documentation of his status was included in his pension application; curiously, the one dated 1820, confirmed by Garrit Gilbert, Register of the City of New York, has Hercules born in “East-Chester,” New York.

This was the hometown of many descendants of John Archer who was originally awarded the patent for the manor of “Fordham” and by family tree branches possibly linked to Caleb Archer, a Westchester County Loyalist.

So maybe his ties to Putnam County were just a moment in time, but his curious story continues with an indomitable spirit and enlightenment.

During his years in Manhattan, Hercules became a preacher “of the Methodist persuasion” with Bethel Church, the African Methodist Episcopal Church on Elizabeth Street. Testimony for his pension application was provided by his pastor, Reverend Samuel Todd, and fellow church member Abraham Mark.

In 1832 Congress enacted liberal pension legislation and Hercules was encouraged by his friends and neighbors to finally apply for benefits. All leads to his family ties are lost and by this time, he was approximately 79 years old, in failing health, fragile memory, and impoverished.

The application process was long and drawn out.

By January 1840, Congressman Ogden Hoffman petitioned the Commissioner of Pensions to further investigate the then upwards of 90-year-old Hercules’ pension application as he was suffering from old age and was destitute. Unfortunately, his pension was ultimately denied with the record stating, “suspended for defective proof – but he was a slave, and there is no evidence that he was emancipated before his discharge.”

During this same period, Maria Jay Banyer (1782-1856), daughter of the Revolutionary leader and first Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court, John Jay, set forth funds for the “relief of the sick and respectable Colored Aged.”

By 1840, the city of New York opened The Colored Home (The Home for the Colored Aged, later Lincoln Hospital) to provide “protection and a peaceful home for the respectable, worn-out colored servants of both sexes of our city, by sheltering and sustaining them during the lingering days of declining life.”

By 1840, the city of New York opened The Colored Home (The Home for the Colored Aged, later Lincoln Hospital) to provide “protection and a peaceful home for the respectable, worn-out colored servants of both sexes of our city, by sheltering and sustaining them during the lingering days of declining life.”

Hercules Schureman was one of the earliest “pensioners,” or residents, of the home.

Years later, a history of this home was recorded by Mary W. Thompson entitled, “Broken Gloom: Sketches of the history, character, and dying testimony of beneficiaries of the Colored Home”. The introduction stated that the home was based on charity and “consolations of religion,” to advance “the moral culture and physical condition of those… whom Providence has thrown upon our charities.”

Among the eighteen biographical sketches, is Hercules, by then a centenarian. According to the book’s romanticized account, he was noted as once a slave but “by his industry and good conduct, purchased his freedom, became a minister of the Gospel in the Methodist connection, and for more than fifty years he preached Christ, and proclaimed to his dying fellow-men, the grace of God which bringeth salvation, and “that liberty herewith Christ maketh his people free.” Broken Gloom reported that when he died, Hercules was over 100-years-old.

According to the History of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, written in 1891, in 1845 a meeting of the New York churches was held and in it was a special acknowledgement that “Brother Hercules Schureman,” the grandfather of Rev. Wm. D.W. Schureman (son of Rev. Peter D. W. Schureman, whose freedom was purchased by his father in 1795) “was one of the two ministers called to their reward this year. He was nearly one hundred years of age.”

According to the History of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, written in 1891, in 1845 a meeting of the New York churches was held and in it was a special acknowledgement that “Brother Hercules Schureman,” the grandfather of Rev. Wm. D.W. Schureman (son of Rev. Peter D. W. Schureman, whose freedom was purchased by his father in 1795) “was one of the two ministers called to their reward this year. He was nearly one hundred years of age.”

After all his trials and tribulations, including slavery, revolutionary military service, having to obtain his own freedom twice, and being denied a pension – it may be that Hercules’s greatest legacy is his family who persevered for generations preaching with great power and strength through their faith.

Brewster High School student, Roderick Cassidy Jr., 18, has been participating in the National Archives Citizen Archivist Missions to help tag and transcribe records relating to Putnam County, New York’s Revolutionary War records. With the extra eyes of historian parents, he’s helping unlock the sometimes-tricky cursive and difficult to read text of pension records. Thanks to the Citizen Archivist Missions, many topics are transcribed creating metadata added to the National Archives Catalog which then become searchable in Google or other search engines, making the archives more accessible online. He hopes to pursue history and social studies in college.

Illustration, from above: 1867 Beers Map of Putnam County showing Putnam Valley and Phillipstown; Hercules Schureman in the 1800 Federal Census; Schureman’s freedom details from Exhibit A in his pension application; “The Colored Home,” aka Home for the Colored Aged, later Lincoln Hospital (Library of Congress); and Hercules Schureman’s grandson Rev. William D.W. Schureman (New York Public Library).