By Roger LuckhurstFeatures correspondent

AMC

AMCZombies have a habit of coming back – as witnessed with the premiere of The Walking Dead: The Ones Who Live, a new spinoff series in the TV franchise. They tap into trauma in US history.

Fans of the undead are abuzz because The Walking Dead: The Ones Who Live – the latest spin-off of the post-apocalyptic TV series – has just premiered in the US. The sixth spin-off and seventh television series in the franchise, it’s set after the conclusion of the original series, with Andrew Lincoln and Danai Gurira returning as Rick and Michonne.

Despite some critics arguing that it’s “not quite the grand comeback we were hoping for”, others claim the latest Walking Dead is “a powerhouse showcase” for Lincoln and Gurira, and a treat for longtime fans. Of which there are many: the original series ran from 2010 to 2022, becoming one of cable TV’s biggest ever series, and has been revived many times since. Because one thing we know about the zombies is that they have the habit of always coming back. We are not done with this creature yet.

More like this:

– What will be the next Walking Dead?

Where did all this come from? It is common to trace the contemporary zombie back to George Romero’s 1968 B-movie shocker, Night of the Living Dead. In fact, that film never uses the z-word and was a very loose adaptation of Richard Matheson’s vampire novel, I Am Legend, where the last human alive attempts to find a cure for the vampire virus.

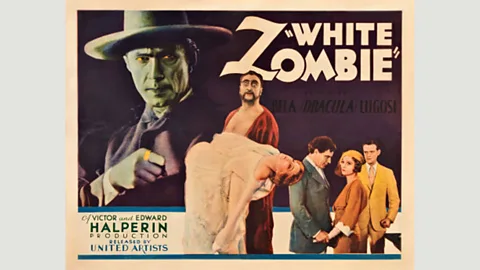

Histories of the zombie film suggest a beginning further back, in Victor Halperin’s White Zombie, which first appeared in 1932 within months of Universal Studios’ famous adaptations of Frankenstein and Dracula. In White Zombie there are lots of laborious explanations of the zombie for the US audience because it transports into the popular culture a set of beliefs from Haiti and the French Antilles in the Caribbean. Today’s zombie is the result of this translation.

Alamy

AlamyThere is some speculation that the word derives from West African languages – ndzumbi means “corpse” in the Mitsogo language of Gabon, and nzambi means the “spirit of a dead person” in the Kongo language. These were the areas where European slavers forcibly transported vast numbers of the population across the Atlantic to work in the sugar cane plantations of the West Indies, the vast profits of which motored the rise of France and England to world powers. The Africans took their religion with them. However, French law required slaves to convert to Catholicism. What emerged was a series of elaborate synthetic religions, creatively mixing elements of different traditions: Vodou or Voodoo in Haiti, Obeah in Jamaica, Santeria in Cuba.

What is a zombie? In Martinique and Haiti, it could be a general term for spirit or ghost, any disturbing presence at night that could take myriad forms. But it has gradually coalesced around the belief that a bokor or witch-doctor can render their victim apparently dead – either through magic, powerful hypnotic suggestion, or perhaps a secret potion – and then revive them as their personal slaves, since their soul or will has been captured. The zombie, in effect, is the logical outcome of being a slave: without will, without name, and trapped in a living death of unending labour.

Dawn of the dead

The imperial nations of the North became obsessed with Voodoo in Haiti for one very good reason. Conditions in the French colony were so dreadful, the death rate amongst slaves so high, that a slave rebellion eventually overthrew their masters in 1791. Re-named Haiti from the French Saint-Domingue, the nation became the first independent black republic following a long revolutionary war in 1804. From then on, it was consistently demonised as a place of violence, superstition and death because its very existence was an offence to European empires. Throughout the 19th Century, reports of cannibalism, human sacrifice and dangerous mystical rites in Haiti were constant.

United Artists

United ArtistsIt was only in the 20th Century, after the US occupied Haiti in 1915, that these stories and rumours began to coalesce around the “zombie”. US forces attempted a systematic destruction of the native religion of Voodoo, which of course only reinforced its power. It is significant that White Zombie appeared in 1932, right at the end of the US occupation of Haiti (the troops left in 1934). America went in to “modernise” a country they considered backward – but instead returned home carrying this “primitive” superstition.

US pulp magazines of the 1920s and ’30s were increasingly full of tales of the vengeful undead, climbing out of the grave and chasing down their killers. These had once been immaterial spectres: now they were the very physical form of rotting corpses said to be lurching out of Haitian cemeteries.

However, it wasn’t pulp fiction that really brought the zombie into the pantheon of the US supernatural. Two key writers at the end of the ’20s not only travelled to Haiti but also – sensationally – claimed to have encountered actual zombies. This was not just an imaginary Gothic thrill: zombies, they claimed, really existed.

United Artists

United ArtistsThe travel writer, journalist, occultist and alcoholic William Seabrook went to Haiti in 1927 and wrote The Magic Island about his trip. Seabrook had danced with whirling dervishes in Arabia and tried to join a cannibal cult in West Africa. In Haiti, he was soon initiated into Voodoo ceremonies and claimed to have been possessed by the gods. Then in one chapter called Dead Men Working in Cane Fields, the mention of zombies prompts a local to take Seabrook to the plantation of the Haitian-American Sugar Corporation and introduce him to the “zombies” who work the fields at night. “The eyes were the worst. They were in truth like the eyes of a dead man, not blind, but staring, unfocused, unseeing.” Seabrook panics, momentarily, that all the superstitions he had heard are true, before plucking for a rational explanation: they were “nothing but poor ordinary demented human beings, forced to toil in the fields”. This chapter became the basis for White Zombie, and Seabrook often claimed he was responsible for bringing the word into the US vernacular.

A legend that won’t die

The other writer was the esteemed black novelist Zora Neale Hurston. Many of the Harlem Renaissance writers of the 1920s and ’30s were interested in Haiti as a model of black independence, and campaigned against US occupation. Hurston was more conservative and thought the occupation was a good thing. Rather more remarkably, Hurston trained as a professional anthropologist and was sent first to study “Hoodoo” in New Orleans (the African-American version of Voodoo in the bayous) and then spent several months in Haiti, training to be a Voodoo priest. She became increasingly spooked by her experiences, although her anthropological reports are cagey about these moments.

Screen Gems

Screen GemsThen in her informal travel book about Haiti, Tell My Horse (1937), Hurston not only informs us that zombies exist, but that “I had the rare opportunity to see and touch an authentic case. I listened to the broken noises in its throat, and then, I did what no one else has ever done, I photographed it.” The image of Felicia Felix-Mentor, the “real-life” zombie, is indeed truly haunting. Pretty soon after this meeting, Hurston left Haiti hurriedly, believing that secret voodoo societies were intent on poisoning her.

If Hurston did encounter a zombie in Haiti, the poor woman she captured with her camera might have been not so much an undead creature as a person who had suffered social death, cast out by her community and perhaps suffering from profound mental illness (Hurston met her in one of Haiti’s mental hospitals). Nevertheless, the historical trauma of slavery underpins this terrible condition of being emptied out of the self, a woman without attachments left shuffling through a living death.

The Walking Dead, too, carries the echo of this history. The series rarely made much of the setting, but various knots of survivors passed through Georgia, through abandoned landscapes that once housed huge slave plantations. To understand the history of the zombie is to understand the anxieties this figure still addresses in contemporary US culture, where race remains a matter of deadly serious importance.

Roger Luckhurst’s Zombies: A Cultural History is out from Reaktion Press.

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can’t-miss news delivered to your inbox every Friday.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.