Shakespeare’s King Lear has defied composers who refused invitations to render this bleakest of tragedies into opera: Berlioz, Britten, Verdi were all at some point approached about an operatic version, all declined the opportunity. Aribert Reimann had no such doubts, however, rendering a composition, first performed in 1978, filled with rage and fury. With a German-language libretto by Claus H. Henneberg, it’s an abrasive, in-yer-face, work: direct, aggressive and brutal. It can appear a relentless experience for an audience, plunged into the intensity of a family drama with cruel consequences where the music appears to have the force of the storm scene over much of the ensuing action. Shakespeare’s five-act play, compressed into an intense two-act opera, focuses relentlessly on Lear’s descent into madness with little respite or humour.

Calixto Bieito’s new reading, a co-production between Teatro Real and the Opera de Paris brings a constrained focus to the piece. Lear is, on one level, an opera well suited to Calixto Bieito’s aesthetic – one that has provided bleak, topical readings of canonical works that have both enthused and frustrated audiences. Here, turning to a modern classic, the visual excesses and energetic choreography that often marks his stagings are replaced by a more austere performance register, something that allows the aggression of the percussion heavy music to resonate. Rebecca Ringst’s set provides a sombre empty room at the opera’s opening where Bo Skovhus’s imposing Lear summons his three daughters to declare their love for him in return for a share of his kingdom. The set recalls that of Brook’s 1971 film of Shakespeare’s play in its unadorned simplicity. A tall structure of wooden beams bound together creates a sense of imprisonment, particularly when the beams move to suggest a metaphorical prison incarcerating Lear in the storm scene. There is something of a post-war existentialism in the decor – something which recalls Jan Kott’s reading of Shakespeare as our contemporary. It suggests a bleak wasteland, an empty landscape where Skovhus’s Lear holds court. Ingo Krügler’s costumes have something of a contemporary feel while suggesting a cut that harks back to the 1950s.

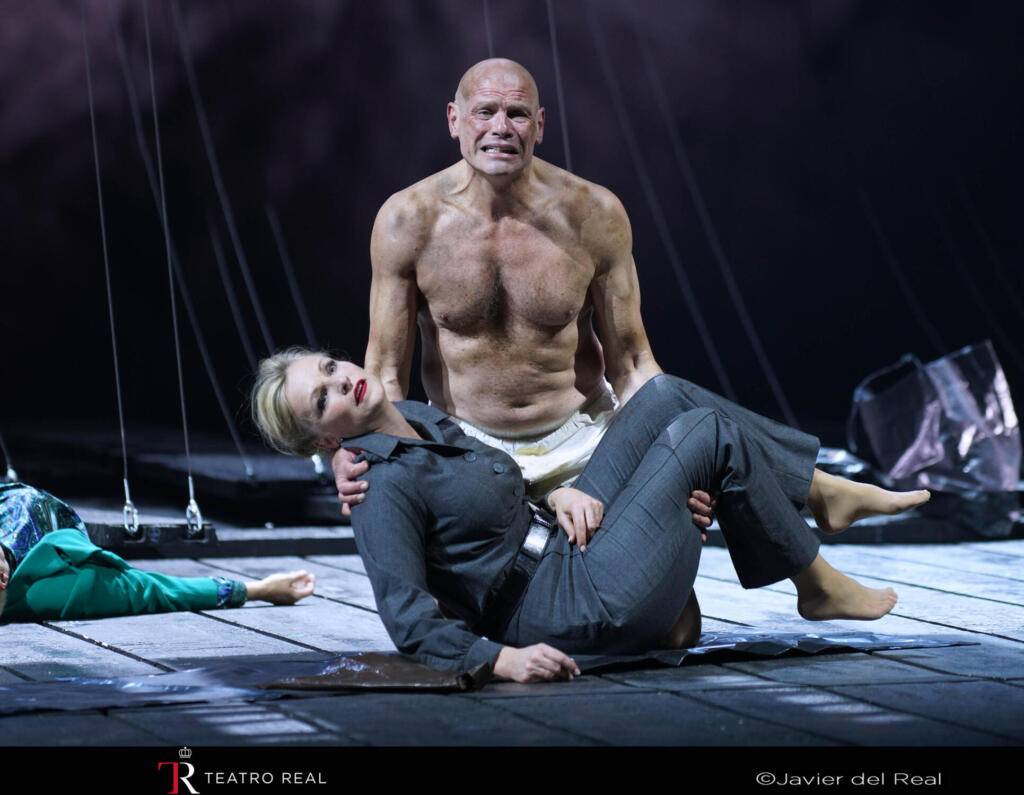

This monarch has something of a brash gangster about him, throwing parts of a loaf of bread at his avaricious elder daughters, which they eagerly devour as they swallow up parts of his kingdom. This is a family who operate through extremes. Ángeles Blancas’s Goneril stands firm and unmovable in her brash green suit. Erika Sunnegårdh’s Regan falls to her knees, crawling to her father in desperation as she professes her undying devotion. Susanne Elmark’s Cordelia stands slightly to the side, listening and observing with a sense of impending horror at the unravelling farce. When she doesn’t give her father the answer he expects, he viciously sits on her and drags her across the floor in frustration. It’s a gesture of marked aggression recalling Lear’s humiliation of Cordelia in Bieito’s earlier 2004 production of Shakespeare’s 1605 tragedy. Twenty years ago, Bieito presented the family as a something of a vestige from the Cold War. This family seems to operate in a more gangster-like terrain: violence as the answer to any and all disputes. When Lear tosses Goneril and Regan the portion of bread that was to have been Cordelia’s, they pounce on it like starving dogs. This Cordelia reaches out to him with concern, but he aggressively pushes her away: there is no room for tenderness in his absolutist world.

Ernst Alisch’s Fool is a speaking role, a chorus-like figure who watches the action unfold with a weary sense of deja vu. Bare chested, in black formal trousers and a trim trilby, he appears to have stepped out of Waiting for Godot. At times, he moves as if he might be preparing to take the stage for a Weimar cabaret show. Lauri Vasar’s stiff Gloucester stares ahead without realising what Andreas Conrad’s Edmund is plotting and planning around him. His fixed glance suggests a man unable to assess what surrounds him. This is an impressive cast who execute their roles with skill, providing each character with a distinct personality both gesturally and vocally. Sunnegårdh’s Regan is a consistently antagonistic figure – lashing out at Goneril and anyone else who stands in her way. Blancas’s Goneril is more calculating, more menacing. Kor-Jan Dusseljee’s Kent, disguised following his banishment in a battered tracksuit, is largely impotent, unable to stop the tragedy unfolding — it’s a brilliant conception of the role. Lear reaches out to his elder daughters when he visits their homes, but Goneril just pushes him away in disgust: the imposing monarch reduced to a plaything thrown from sister to sister.

The beams of wood that contained the action in the first section of the action, move and slide during the storm scene. They hover menacingly over Lear and his entourage as the errant troupe seek protection from the elements. The impression is that of an imposing forest of dense trees that offer little chance of escape. Indeed, they protrude out as if signalling the impending danger for Lear. Andrew Watts’ Edgar is a jittery figure, dressed in soiled underwear, whose games with Lear in the storm under a filthy tarpaulin conjure something of a dysfunctional music hall double act. He leads Lear out backwards, like crustaceans in search of safely on a beach full of predators.

Lear (Bo Skovhus) cradles the dead Cordelia (Susanne Elmark) in Lear: Photo Javier del Real / Teatro Real Madrid

In Act 2, the action accelerates to its terrible denouement. Goneril and Regan both lust over Andreas Conrad’s scheming Edmund – he has inherited something of his father’s awkward stance but without any of the sense of duty. Goneril lacks Regan’s physicality, her declarations to Edmund boasting a rigidity that complements her demeanour. Regan plucks out Gloucester’s eyes with demonic joy, laughing manically as she does so. Susanne Elmark’s Cordelia brings a more tranquil energy into the room on her return from France, a new compassion that is reflected in the writing for strings — a lyrical line that tones down the feverish energy of the earlier scenes of abuse. Lear — who has jumped and swung, pulled and pushed — lies down in exhaustion for the returning Cordelia to find him. Their reunion, contains the opera’s most beautiful music: a passage for tutti strings playing a sustained meandering unison melody is a rare moment of poignant beauty and empathetic forgiveness in this otherwise relentlessly violent percussion-driven score. Regan’s strangling of Cordelia — here an onstage act — is uncompromising in its brutality. Goneril, after administering the poison that leads to Regan’s violent death, strangles herself with her own scarf. The end comes with no words of comfort, no indication of the new world ahead led by Albany and Edgar. Lear’s death closes the opera — a body on stage, discarded and alone. No mourning, no hope. Just emptiness.

Asher Fisch presides over the score with a precision and vitality that emphasises the musical violence of the opera, punctuated by moments of poignant lyricism. In the title role, Bo Scovhus, onstage for the majority of the opera’s 150 minutes, sings with astonishing power and pathos in his descent from arrogant king to demented old man. He is supported by fine and incisive singing particularly from Andreas Conrad’s clinical Edmund, Andrew Watt’s stylish Edgar and Michael Colvin’s pitiless Cornwall. Franck Evin’s lighting allows for both intense pockets of action and at times a brash sense of brutish surveillance which no character can escape. Sarah Derendinger’s video projections in the production’s final scenes suggest an oceanic tranquillity that lies in sharp contrast to the raging music. The production’s strength lies in deploying the different elements of performance to persuasive effect in chronicling Lear’s downfall. It’s a sobering experience distinguished by a brilliant theatrical and musical execution. Bieito renders Reimann’s Lear an unexpectedly timely work where redemption does not equate with solace and abuse does not always go unpunished. In an uncertain world of shifting plates, it feels eerily contemporary.

Lear played at the Teatro Real Madrid from to 26 January to 7 February 2024.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Maria Delgado.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.