By Beverley D’SilvaFeatures correspondent

Steve Morgan/ National Railway Museum

Steve Morgan/ National Railway MuseumBritain’s most famous steam locomotive turned 100 this year, and along the way it has inspired poets, Hitchcock, Harry Potter and Royalty. What makes it such an enduring icon?

Some grow misty-eyed with nostalgia at the mere mention of them, waiting for hours on a windy platform just to get a glimpse or a photo of these stars of a bygone age. Others find them smelly, dirty, and their hooting and screeching too much to bear. We’re talking about steam engines, and although travelling by locomotive may be a rare treat for most, the golden age of steam is being kept alive at the many heritage railways around the world, with more than 30 still running in the UK alone.

More like this:

Firmly in the steam-age fan camp is presenter and author Michael Palin – a self-confessed train spotter who, in a 1980 BBC documentary, reflected: “I suppose true railway buffs love all engines – short, fat, squat, long. Rumbling smelly diesels or swiftly silent electrics. But most of all, they love steam… And the most famous steam engine of them all is the Flying Scotsman.”

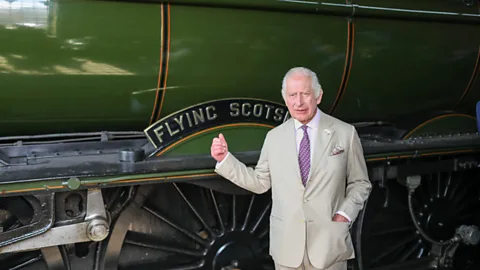

Today, the Flying Scotsman is still arguably the most famous steam locomotive on the planet, drawing huge crowds whenever it makes an appearance. Since it turned 100 in February, there have been celebrations and steam-related events to mark its grand old age, including a visit by the King in June; culminating in a Christmas programme of excursions at the National Rail Museum, which owns it. Not to mention an illustrated children’s book on the steam age by Michael Morpurgo; a tribute poem by Simon Armitage; and a new film featuring those whose lives have been touched by it.

Steve Morgan/ Science Museum Group

Steve Morgan/ Science Museum GroupWhat is it about the Flying Scotsman that has led to its enduring fame and popularity above all other steam engines? Why has it earned a place in the hearts of many nations, but especially the Brits? The locomotive’s history has had many highs and lows, and a moment when it seemed destined for the scrapheap, only to be saved for the modern age.

Completed in February 1923, at a cost of almost £8,000, the Flying Scotsman was originally built by the London and North Eastern Railway (LNER), to a design by its chief engineer, Sir Nigel Gresley. It weighed 97 tonnes, was 70ft in length, and was one of the Pacific type (class A1) express tender locomotives – the most powerful used by the railway.

It was not, in fact, built in Scotland, as many believe, but in Doncaster in the north of England; and the story behind its naming holds a clue to its early fame, says Andrew Mclean, chief curator at the National Railway Museum (NRM) in York. “The locomotive was deliberately named by the LNER after the ‘Flying Scotsman’, which was the unofficial name of its famous flagship service, the Special Scotch Express; launched in 1852, it ran daily from London’s King’s Cross to Edinburgh,” he says. LNER advertised that service as “The Most Famous Train in the World”; that, coupled with the public’s confusion over the difference between a locomotive and a train, boosted its fame no end. (To clarify, Scotsman is a locomotive or engine, and pulls the carriages of a train.)

“Scotsman was not revolutionary in the way George and Robert Stephenson’s Rocket was,” says Mclean, referring to the 1829 steam locomotive considered the greatest innovation of the Victorian era. “Nor was it the largest, most powerful or fastest.”

Steve Morgan/ Science Museum Group

Steve Morgan/ Science Museum GroupBeing selected for the British Empire Exhibition in Wembley in 1924 kickstarted its fame, and since then it has broken numerous records. In 1928, it hauled the first nonstop run of the northbound Flying Scotsman train service; in 1934 it set the world steam speed record of 100mph (though it was beaten a year later by Papyrus, a sister loco); in Australia it made the longest non-stop run by a steam locomotive at 422 miles in 1989; on the way back to England the next year, it became the first steam locomotive to circumnavigate the globe (with the aid of a ship, of course).

But it’s not all been about piston-pumping strength – or as Poet Laureate Armitage puts it in his paean to the engine: “its vast steel circumferences, straining, hissing, the rippling bodywork pouring with sweat, skirts trimmed with petticoats of steam”. Scotsman has been sprinkled with glamour and media innovation too, pulling trains on which cinema, radio and television were trialled, as well as a Louis XV-style restaurant and even a cocktail bar.

Charisma and drama

If an engine can have charisma and drama, it was first realised in the eponymously titled 1930 film, one of Britain’s first “Talkies”. It’s astonishing now to imagine that actress Pauline Johnson was allowed to do her own stunts for it, clinging to the outside of the speeding loco. Director Alfred Hitchcock gave it a key role in his 1935 spy suspense film, The 39 Steps, as Robert Donat’s character flees from assassins by boarding a Scotsman-led train from London to Edinburgh. As this century dawned, it was the role model for Harry Potter’s Hogwarts Express, it has been claimed, famously arriving on platform 9¾ at King’s Cross, and now on public show at Warner Bros studio tour London.

Steve Morgan/ Science Museum Group

Steve Morgan/ Science Museum GroupHogwarts’ engine is red – not a Scotsman hue. Its original colour was apple green, and in World War Two it was repainted wartime black, like all railway stock, returning to green after the war. It was all change again in 1948, when British Railways (BR) was formed, and UK rail travel was nationalised; the Scotsman was painted blue for a time, then BR Green, and numbered 60103 (its sixth and current number).

BR’s modernisation in 1955 sounded a death knell for the steam age, and 1962 was the Scotsman’s last full year of service. BR’s last mainline steam-hauled passenger train ran on 11 August 1968. That evening, a documentary commemorated the end of the steam age, and among passengers travelling on Scotsman’s non-stop from London to Edinburgh was the Reverend W Awdrey, who mourned the end of steam in one of his celebrated Thomas the Tank Engine stories, illustrated by John T Kenney.

Scotsman could have been consigned to the great loco scrapyard in the sky, but for a programme on its plight in 1966 on Blue Peter, the popular BBC children’s series, that was prompted by thousands of children writing in protest. That, coupled with a growing interest in national heritage, led to it being rescued and restored by steam-loving businessmen, including Alan Pegler, Sir William McAlpine, and later pop music producer Pete Waterman. In 2004 it was acquired by the NRM, its future safe for now.

Steve Morgan/ Science Museum Group

Steve Morgan/ Science Museum GroupThe Scotsman may be a national treasure, but it’s not without competition. “There’s one locomotive that may draw a higher appeal and that would be Mallard,” says Mclean referring to the fastest steam locomotive in the world. That doesn’t seem to dent the Scotsman’s appeal to enthusiastic crowds who cheer it on whenever it appears on tours of the US, Canada and Australia. When not on exhibit at the NMR in York, England, it can be found pulling excursions along the mainline or on British tourist railroads.

Steve Morgan was the official photographer who documented Scotsman’s centenary, and witnessed first-hand the excitement it can generate: “I was amazed by its popularity,” he says, “and by the people who love it, from traditional steam engine freaks to young girls and women. They all seem to have a very personal attachment to it.”

Besides photographing the King with Scotsman and its crew, Morgan captured it being restored and maintained, giving an idea of its great size; and the women train drivers who took charge of it as part of International Women’s Day. In the name of research, he even managed to squeeze into the engine’s firebox, into which the fireman has the hard physical task of shovelling tonnes of coal. “It was smelly and dirty, as you’d imagine, but fascinating too.” The coal used was once supplied by British mines until they shut down, and until recent years came from Russia; now it mostly comes from Poland and Czechia. The use of bio coal is being considered, says Mclean.

Morgan adds: “Yes, there is a degree of nostalgia attached to it, and harking back to a bygone age. But what’s remarkable is that Scotsman still does its thing. It has a life and an energy about it that a lot of other machines just don’t.”

Mclean mulls over what Scotsman might mean to the Scottish people. Its name is perhaps confusing, since “it only ran in service to Scotland for 10 years, from 1925 to 1935 – and then didn’t make it over the border again until well into the 1960s”. He says in recent years, images of the Flying Scotsman puffing across the Forth Bridge have “probably reinforced the idea that it’s a Scottish icon, and the fact its designer, Gresley, was born in Edinburgh”.

Steve Morgan/ Science Museum Group

Steve Morgan/ Science Museum GroupOn the other hand, he adds: “When it toured north America in the 1960s, it was billed as a British Trade Mission and was seen as symbolic of Britishness. [It toured] along with some mixed stereotypes including a butler hired from Fortnum and Mason, a Pipe Major, a man dressed in a suit of armour and, bizarrely, a Winston Churchill impersonator played by Churchill’s own nephew.” Perhaps one of the iconic steam engine’s greatest achievements is being a survivor, and its most recent record is as the oldest locomotive to travel on British railway tracks. It shows no sign of stopping doing what it does best.

“When you think about it, we’ve got these great symbols of British engineering and innovation, like Concorde and the Queen Mary,” says Mclean. “But while you can no longer travel in either of those, you can still travel by Flying Scotsman, which is pretty incredible.”

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can’t-miss news delivered to your inbox every Friday.