For the Union Army of the Potomac and its commander, Maj. Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside, the early winter of 1862-63 proved extremely taxing. First, they suffered through the disastrous Battle of Fredericksburg, fought on Dec. 13. After the army retired back across the Rappahannock River, regimental musters revealed a staggering loss of 12,653 casualties. Nothing had been gained. It had all been for naught. Army morale plummeted, and desertions soared, eventually reaching 200 per day. Tens of thousands of men were listed as “not present”: thousands of others were sick due to inadequate food and the army’s abysmally filthy camps.

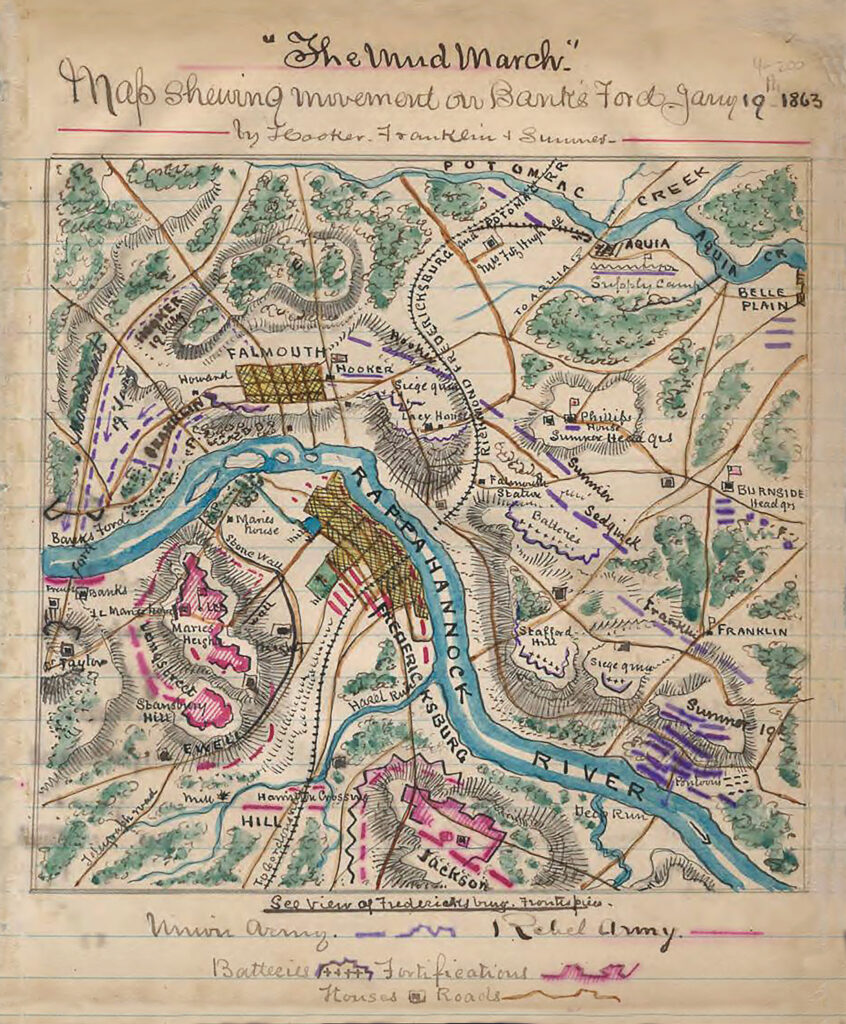

Then came Burnside’s infamous “Mud March.” In an attempt to flank the opposing Army of Northern Virginia out of its positions behind the Rappahannock, Burnside ordered an upriver movement via Banks’ Ford. It began on Jan. 20, but that night, the heavens opened up. In the following two-day deluge, small streams became raging torrents. Roads turned into muck-filled quagmires choked with stalled wagons, pontoons, artillery pieces, and hundreds of buried horses and mules. Drenched, freezing, exhausted—feeling as if the very fates were against them—the rank and file dragged themselves back to their encampments at Falmouth. Everyone realized the army was dispirited; many believed it was “all played out.” For the Army of the Potomac, the early winter of 1862-63 was indeed the Valley Forge of the Civil War.

Enter the army’s next head, Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker. Most often remembered as the bombastic commander who lost the subsequent Battle of Chancellorsville (May 1-4), despite outnumbering his opponent two to one, Hooker, nonetheless, possessed admirable administrative and organizational skills. And what’s little remembered is that—in the three months leading up to Chancellorsville—he did a fantastic job restoring the army’s morale and preparing it for the upcoming campaign. Maj. Gen. George Brinton McClellan built the Army of the Potomac, but Maj. Gen. Hooker rehabilitated it.

“The Handsome Captain”

Born in Hadley, Massachusetts, in 1814—the grandson of a Continental Army captain—Hooker graduated from West Point in 1837. Commissioned 2nd Lt. in the 1st U.S. Artillery, he first served brief stints in Florida, on the frontier, and as adjutant at his alma mater. During the Mexican-American War (1846-48), Hooker proved an able and courageous staff officer, winning three brevet promotions. It was in Mexico, too, that the well-proportioned six-foot-tall officer first became known as a ladies’ man: the señoritas there nicknamed him the “handsome captain.”

In California after the war, Hooker served briefly as assistant adjutant general of the Army’s Pacific Division, then, following a leave of absence, resigned his commission to work the land. Unsuccessful as a farmer, he moved to Oregon, where he held the position of superintendent of the territory’s military roads for two years. The last years of the 1850s found Hooker serving as a colonel in the California State Militia. When the Civil War exploded onto center stage in 1861, he raised a regiment of Union volunteers to bring east but was extremely disappointed to learn that California units weren’t eligible for such service. He was determined to travel east and renew his affiliation with the Army, but high living had reduced him to poverty. Thankfully, his friends—among them a San Francisco tavernkeeper—staked him $1,000 and sent him off by steamboat.

In Washington, Hooker presented his credentials to President Abraham Lincoln and 75-year-old Winfield Scott, the Army’s commanding general. But there was a snag. At the termination of the war with Mexico, Hooker had testified in defense of an officer Scott had charged with disloyalty. This had angered Scott, and unfortunately, Scott still remembered. Forced to cool his heels in the War Department anterooms, Hooker nonetheless witnessed the First Battle of Bull Run as a civilian.

Soon thereafter, in an audience with Lincoln, Hooker first complained that, evidently, the Army didn’t want him back. Then he boldly asserted: “I was at Bull Run, the other day, Mr. President, and it is no vanity or boasting in me to say that I am a damned sight better General than you, Sir, had on that field!”

(Library of Congress)

Made a brigadier general on Aug. 3, 1861, his commission backdated to May 17; he was first posted to the fortifications northeast of Washington City, where he drilled his regiments rigorously. In October, Brig. Gen. Hooker was put in charge of a 10,000-man division and charged with defending the lower Potomac River. This exceedingly dull duty involved primarily the interdiction of illicit mail and trade.

The following year, in mid-March, Hooker’s division was assigned to the III Corps of Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan’s Army of the Potomac. Landing on the Virginia Peninsula in April, Hooker’s men dug in opposite the Confederate position at Yorktown.

During the subsequent Peninsula Campaign, Hooker, now a major general, frequently displayed his aggressive and boastful nature—rashly attacking the superior forces of the enemy rearguard at the Battle of Williamsburg on May 5, for example, and later confidently messaging McClellan that he could hold his position in front of Richmond “against 100,000 men.”

Fighting Joe

It was during the Peninsula Campaign that Hooker received his enduring nickname. The standard tale was that a New York newspaper’s compositor accidentally set a telegraphed headline reading “Fighting—Joe Hooker” (meaning it was a continuation of a previous piece) as “Fighting Joe Hooker.” That story now appears apocryphal—several historians have searched archives in vain for said headline. “A reasonable conclusion,” wrote biographer Walter H. Hebert, “is that in some spontaneous manner it was applied to Hooker after Williamsburg.” Perhaps surprisingly, Joseph Hooker was mortified by the name, saying that people would think him “a highwayman or bandit.” (And, to debunk another nickname associated with Hooker: There’s no truth to the story that ladies of the night became known as “hookers” because so many swarmed around Fighting Joe’s encampments. The first known use of “hooker” for prostitute dates to 1845, 16 years before he became a public figure.)

Hooker fought at the Second Battle of Bull Run (August 29-30), and when the Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia crossed the Potomac River into Maryland—Lee’s first invasion of the North—Lincoln and a few of his Cabinet officers considered appointing him to command the Army of the Potomac. Postmaster General Montgomery Blair ended the discussion, however, with the blunt condemnation that Hooker was “too great a friend of John Barleycorn.”

At the beginning of the Maryland Campaign, Hooker was put in charge of the army’s V Corps, a sizeable 15,000-man force. Soon redesignated as the I Corps of Gen. McClellan’s Army of the Potomac, Hooker’s command fought at Turner’s Gap (on Sept.14) and the Battle of Antietam three days later. There, during the desperate fighting in the Miller cornfield, Fighting Joe’s divisions were shattered, the general himself receiving an incapacitating wound to the foot. While convalescing, he was visited by numerous government officials, including President Abraham Lincoln. Hearing rumors that he was again being considered for army command, Hooker—never shy about self-promotion—pressed his case by attacking McClellan’s generalship.

Lincoln’s Choice

Instead, of course, Lincoln replaced McClellan with Maj. Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside, an 1847 West Point graduate with a somewhat checkered battlefield résumé. Taking over in November 1862, Burnside reorganized the Army of the Potomac into four massive “grand divisions,” each comprising two army corps as well as attached artillery and cavalry. Hooker’s Center Grand Division, totaling about 40,000 men, contained Maj. Gen. George Stoneman’s III Corps and the V Corps under Maj. Gen. Daniel Butterfield.

(Library of Congress)

During the catastrophic Battle of Fredericksburg, Fighting Joe’s Center Grand Division was at first held in reserve, then sent in piecemeal. One of his divisions suffered twenty-five percent casualties in a useless assault against Marye’s Heights (quite possibly the Civil War’s strongest defensive position). On Dec. 13, the Confederates at Marye’s Heights—infantry sheltered behind a stonewall along the base of the rise, dug-in artillery on top—easily annihilated fourteen separate Federal attacks. Seven thousand Union casualties were needlessly lost on this part of the battlefield.

Angered over Burnside’s mishandling of the army, Hooker attacked him unsparingly, telling the Joint Congressional Committee on the Conduct of the War, for example, that the strength of the Confederate position had been well-known beforehand. There had been no excuse for the bloodletting at Marye’s Heights. Burnside, exasperated by Hooker’s numerous machinations—his denunciations, his flagrant self-promotion, and his call for a dictatorship to save the republic—drafted for Lincoln’s signature an extraordinary document, General Order No. 8.18. It stated in part: “General Joseph Hooker… having been guilty of unjust and unnecessary criticisms of the actions of his superior officers… and having… endeavored to create distrust in the minds of officers who have associated with him, and having… made reports and statements which were calculated to create false impressions… is hereby dismissed from the service of the United States as a man unfit to hold an important commission. …” Additionally, two major generals and five brigadiers, accused of similar military indiscretions, were also to be relieved from duty.

In Washington, Burnside presented General Order No. 8, along with his resignation, to the much-beleaguered Abraham Lincoln, asking him to either approve the order or accept his stepping down. Lincoln replied that he needed time to consult with his advisers. During those deliberations, several officers were considered for the Army of the Potomac’s top slot (although all agreed that Burnside was out). In the end—and despite the strenuous objections of Secretary of War Edwin Stanton and General in Chief Henry Halleck—Lincoln chose Fighting Joe.

On Jan. 25, 1863, news of Hooker’s appointment reached the Army of the Potomac, where it was fairly well received by the rank and file. They saw him as a fighting general. And, thanks to their fondness for Fighting Joe, they were more than willing to overlook his infighting, intemperance, and reportedly low moral character. Many in the army’s highest ranks, however, were not so sanguine. Two of the army’s grand division commanders—major generals Edwin V. Sumner and William B. Franklin—refused to serve under Hooker and were summarily banished from the Army of the Potomac. Burnside was given a leave of absence.

Fresh Veggies

Soon thereafter, Hooker received the famous Jan. 26 letter from President Lincoln. It opened with a listing of the general’s positive qualities—his bravery, his confidence, his ambition. Then the president admonished Hooker for thwarting Burnside at every turn. Next followed an incredible passage: “I have heard, in such way as to believe it,” Honest Abe had written, “of your recently saying that both the Army and the Government needed a Dictator. Of course, it was not for this but in spite of it that I have given you the command. Only those Generals who gain successes, can set up Dictators. What I now ask of you is military success, and I will risk the dictatorship.” The president then promised the government’s utmost support.

On Jan. 28, after a face-to-face with Lincoln in the White House, Hooker returned to his army’s headquarters at Falmouth, just across the Rappahannock from Fredericksburg, to take command. But, as noted above, the Army of the Potomac was in a deplorable state, both physically and mentally. In letters to their families and hometown newspapers, the soldiers grumbled, detailing their woes. One feared they were “fast approaching a mob.” Another, advocating the army’s breakup, wrote that they “may as well abandon this part of Virginia’s bloody soil.”

(Library of Congress)

Despite the task’s enormity, the 48-year-old Joseph Hooker dove into his new responsibilities with a passion. First, he needed a right-hand man, a chief of staff. In General Order No. 2, dated Jan. 29, Hooker appointed Maj. Gen. Daniel Butterfield. (His first choice for the position, Brig. Gen. Charles P. Stone, was still under suspicion thanks to his bungling of the Battle of Ball’s Bluff in October 1861.)

Although not a West Pointer, New Yorker Butterfield—best known as the supposed composer of “Taps”—had risen quickly through the ranks and was part of Hooker’s inner circle, having led the V Corps in Hooker’s Center Grand Division. He possessed solid organizational skills. Retained as chief of artillery was Brig. Gen. Henry J. Hunt (although he was unfortunately limited to administrative responsibilities). The other staff appointments were adjutants and aides-de-camp from Hooker’s earlier commands.

Early on, Hooker tackled the problem most dear to the men in the ranks—food. Rations for an encamped army were supposed to include fresh vegetables, “desiccated” (or dried) vegetables—derisively called “desecrated” by the soldiers—hardtack, salt pork, and coffee. But much of this good food was being sold for cash by the regimental commissaries to people outside the army. The hungry foot soldiers—even some officers—simply went without. To counteract this profiteering, Hooker ordered that henceforth the men would receive fresh vegetables twice and dried legumes once per week.

Additionally, the new commander ordered the erection of camp bakeries, mandating that his soldiers be issued soft bread, or flour, at least four times a week. Commissary officers who failed to comply were required to file a written explanation. Thanks to this new system of accountability, the men quickly noticed an improvement in both the quality and quantity of their rations. “Whatever they thought of Hooker’s other qualities,” wrote historian Bell Wiley, “soldiers highly approved his competency as a provider.”

Teaching the Men To Bathe?

Orders were also issued to improve the vast camps around Falmouth. When first laid out in early winter, little thought had been given to proper sanitation. The foul odors that emanated from the countless log-and-canvas huts are best left undescribed. Now headquarters required the men to bury their garbage every day and dig drainage ditches around every cabin. Latrines were relocated farther from the company streets. Blankets and bedding were to be aired daily, and the canvas roofs removed often so that the sun, and fresh air, might enter. Unimprovable campsites were abandoned. Attention was also paid to the men’s personal hygiene: They were ordered to cut their hair short, bathe twice a week, and change their underclothing at least once every seven days.

Cleaning up brought about quick and noticeable changes. The army’s medical director, Maj. Jonathan Lettermen, reported that in February, cases of potentially fatal diarrhea dropped 32 percent. Cases of typhoid fever—which had run rampant through the filthy encampments—were down twenty-eight percent. By April, scurvy was almost eliminated. Under Letterman’s direction, army hospitals were aired out and renovated. New hospitals were built. Drunken surgeons were discharged. The ill and the slightly wounded were quickly patched up and returned to the ranks.

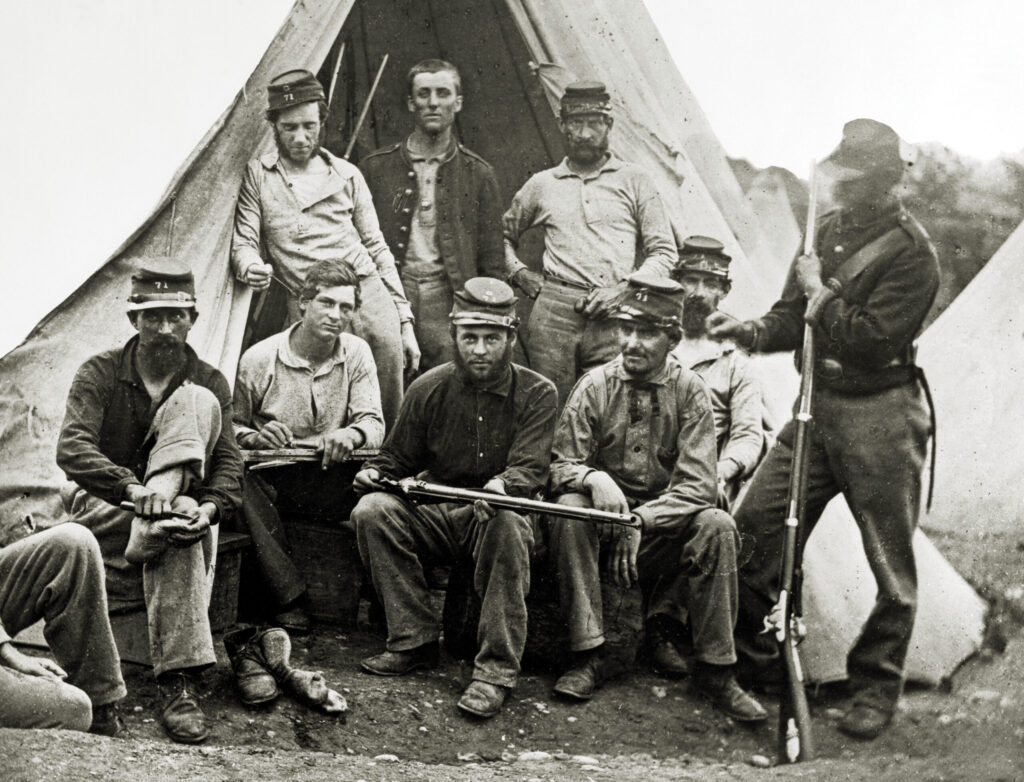

As the men’s health improved, Fighting Joe took steps to keep them occupied. A hectic daily regime of drills and inspections was reinstituted. Company, regimental, and brigade officers studied the manuals by candlelight and put their men through the complicated battlefield evolutions the following day. Of course, the men at first complained—one called the drilling “constant and severe”—but they quickly began to take pride in their improved capabilities. The Falmouth drill fields now witnessed large-scale reviews like those once staged by McClellan.

During these special ceremonies, Fighting Joe Hooker would smile approvingly as the infantrymen marched past him in columns of companies—the men in clean uniforms, their rifled muskets bright. “I believe that the army was never in better condition … than it is now,” noted one Bay Stater, “very different from what it was a month ago.”

(ClassicStock/Getty Images)

Hooker went after the horrendous desertion problem with a carrot-and-stick approach. More than anything else, the soldiers wanted to visit their families back home. Now came a new system—the carrot—under which each company was allowed one ten-day furlough at a time. Additionally, President Lincoln issued an order granting amnesty to absentees who returned to the Army of the Potomac by April. Then there was the stick—programs designed to make desertion difficult and more dangerous. Up to this time, homefolks frequently assisted desertion by simply shipping civilian duds to their soldier boys. Now army-bound packages were under the purview of the provost marshals, and none was allowed past without certification from the shipping agent that it was clothing-free.

Under orders from Hooker, the Army of the Potomac now began stringently enforcing army regulations. Groups of soldiers claiming to be telegraph-repair details needed passes, as did wagons headed north to Washington. Each military unit was ordered to name and physically describe every member who was absent without leave. The outlying picket lines were greatly reinforced—the pickets themselves now ordered to shoot individuals refusing to halt when challenged. Men caught deserting were executed in front of their comrades.

Cheerful Spirits in Camp

Formerly called a “mob,” the Army of the Potomac—thanks to Fighting Joe’s improvements—once again resembled an army. “[C]heerfulness, good order, and military discipline,” wrote one soldier, “at once took the place of grumbling, depression, and want of confidence.” One new development that didn’t sit well with the rank and file, however, was the banishing of liquor from the camps. (And naturally, the officers were excluded from this regulation.) Now the regimental sutlers witnessed booming sales of such items as canned “brandied peaches.” At Washington, bridge guards started seizing five hundred dollars’ worth of alcoholic beverages each and every day.

The most significant structural change to the Army of the Potomac under Hooker was the breaking up of Burnside’s “grand division” formations (of two infantry corps each). As noted above, two of the four grand division heads, major generals Sumner and Franklin, had already departed. (Hooker himself had been another.) The fourth, Maj. Gen. Franz Sigel, took leave of the army at this time due to poor health (and dissatisfaction). Now, army headquarters would issue orders directly to seven infantry corps commanders. (The eighth infantry corps, Burnside’s old IX Corps, still fiercely loyal to “Old Burn,” was ordered away under the command of Maj. Gen. William F. “Baldy” Smith, whom Hooker considered a bad influence.)

While historians have called this reordering detrimental to the army’s success—after all, in 1864, the Army of the Potomac would be reorganized into fewer, larger formations—Hooker’s reasoning at the time appears sound. Based on his Fredericksburg experience, Fighting Joe called the grand divisions cumbersome, predicting that the upcoming campaign would prove “adverse to the movement and operations of heavy columns.” Grand divisions also added another layer to the army’s military hierarchy—meaning orders took longer to filter down to the frontlines.

Four of the army’s infantry corps were given new leaders: Maj. Gen. Daniel E. Sickles—another Hooker crony—assumed command of the III Corps; the V Corps head became Maj. Gen. George G. Meade; Maj. Gen. John Sedgwick was transferred from the exiting IX Corps to lead the VI Corps; and Maj. Gen. O. O. Howard eventually took command of the XI Corps. Four new division heads and nineteen new brigade commanders were appointed. Several of these new leaders were controversial, but nobody could deny that Hooker was breathing new life into the Army of the Potomac.

A huge improvement was now made to the cavalry arm. Under previous commanders, the much-maligned Federal horsemen had been frittered away in inappreciable detachments. Outpost duty, dispatch delivery, and the escorting of general officers had been their lot. Consolidated, they now became a powerful Cavalry Corps under the command of Maj. Gen. George Stoneman. Comprising three divisions of two brigades each, supported by a brigade-sized reserve, this force of over 11,000 proved more than equal to the much-vaunted Confederate cavalrymen at the Battle of Brandy Station on June 9. “From the day of its reorganization under Hooker,” noted an appreciative dragoon, “the cavalry of the Army of the Potomac commenced a new life.”

Expanding on an idea first concocted by Maj. Gen. Philip Kearny (who’d had his soldiers wear squares of red cloth), Chief of Staff Butterfield devised a corps badge system that proved immensely popular. Each corps was assigned a unique emblem—a circle, trefoil, diamond, Maltese cross, St. Andrew’s cross, crescent, or star—that the men attached to their caps. Following the colors of the Stars and Stripes, a corps’ first division wore badges in red, the second division white, and the third blue. The system fostered corps pride and was later invaluable for identifying units in combat.

Joseph Hooker’s leadership transformed the Army of the Potomac. Greatly appreciative, the enlisted personnel began cheering him whenever he rode by on his white charger. As one soldier remembered years later: “Ah! the furloughs and vegetables he gave! How he did understand the road to the soldier’s heart! How he made out of defeated, discouraged, and demoralized men a cheerful, plucky, and defiant army, ready to follow him everywhere!”

(Graphic House/Getty Images)

President Lincoln’s letter of Jan. 26, 1863 had concluded with a brief warning: “Beware of rashness,” Old Abe had written, “but with energy, and sleepless vigilance, go forward, and give us victories.” To Lincoln’s great dismay, however, Fighting Joe went forward and gave the nation the Battle of Chancellorsville, the worst defeat ever suffered by the Army of the Potomac. “My God! My God!” moaned the chief executive, his ashen face filled with sorrow and dread. “What will the country say?”

Under Arrest!

The country had plenty to say—especially when the losses, over 17,000, began to sink in. The New York Herald, for example, worrying about the battle’s “fearful consequences,” blasted Lincoln and his advisers for their “ruinous policy of underrating the enemy. …” And Washington was abuzz with wild rumors: Lee had destroyed Hooker’s army and was advancing on the capital; Fighting Joe was under arrest; McClellan would return to command.

Abraham Lincoln, however, decided to keep Hooker in charge. But when General Lee launched his second invasion of the North and Hooker got into a squabble with the War Department over the status of the Union garrison at Harpers Ferry, Lincoln replaced him with Maj. Gen. George Meade on June 28 (only three days before the commencement of the Battle of Gettysburg).

Despite the career black mark that was Chancellorsville, Hooker was sent west to Chattanooga, Tennessee, in command of the Army of the Potomac’s XI and XII Corps. There he performed admirably at Lookout Mountain on Nov. 24, 1863. The two eastern corps were combined in April 1864 as the XX Corps, Army of the Cumberland, and subsequently, under Hooker’s leadership, participated in the Atlanta Campaign. Passed over for promotion, Hooker submitted his resignation to army head Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman on August 27. “I will not object,” was Sherman’s reaction. “He is not indispensable to our success.”

Hooker sat out the rest of the war in Cincinnati, Ohio, in charge of the army’s Northern Department (which comprised the states of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, and Michigan). The boredom of this duty—securing the Ohio River and the northern frontier—Fighting Joe alleviated by making speeches and wooing Olivia Groesbeck of Cincinnati, whom he married once the fighting was over. Hooker led Lincoln’s funeral procession in Springfield, Illinois, on May 4, 1865, and was greatly heartened that same year when the report of the Congressional Committee on the Conduct of the War exonerated him for the devastating defeat at Chancellorsville.

After the war, he oversaw two of the Army’s large administrative districts: the Department of the East and the Department of the Lakes. Retiring on Oct. 15, 1868, he spent his last decade traveling, attending reunions, and threatening to publish his memoirs. Joseph Hooker—the pompous, hard-drinking officer whose leadership, in only three months, completely revitalized the Army of the Potomac—died suddenly on Oct. 31, 1879. He was buried in Cincinnati’s Spring Grove Cemetery.